After an unfortunate breakup with a woman named Mary Owens, and with negotiations over moving the capital from Vandalia to Springfield under way, Abraham Lincoln decided to leave New Salem for the big city. The move was advantageous.

After an unfortunate breakup with a woman named Mary Owens, and with negotiations over moving the capital from Vandalia to Springfield under way, Abraham Lincoln decided to leave New Salem for the big city. The move was advantageous.

But he was broke. Even with his full pay for the last session of the state legislature in hand, Lincoln rode his old horse to Springfield deep in debt. Upon arrival, one of his companions on the trip, William Butler, sold Lincoln’s horse without telling him, paid off his debts, and moved his saddlebags into the Butler household about fourteen miles out of town. Lincoln continued taking his meals at the Butlers without charge for the next five years. After a while Lincoln decided he needed to find a place in town, and he rode in on a borrowed horse with his saddlebags, a few law books, and the clothes on his back seeking residence. His first stop was Joshua Speed’s store. According to Speed, Lincoln asked “what the furniture for a single bedstead would cost.” Putting pencil to paper, Speed told him the sum would be seventeen dollars. Taken aback, Lincoln agreed it was probably a fair price but replied, “If you will credit me to Christmas, and my experiment here as a lawyer is a success, I will pay you then. If I fail in that I will probably never be able to pay you at all.” Seeing his forlorn look, Speed offered:

I think I can suggest a plan by which you will be able to attain your end, without incurring any debt. I have a very large room, and a very large double-bed in it; which you are perfectly welcome to share with me if you choose.

“Where is your room?” asked Lincoln. Speed pointed to the stairs leading from the store to his room. Saying nothing, Lincoln took his saddlebags, went up the stairs, tossed them on the floor, and returned “beaming with pleasure” to say:

“Well, Speed, I’m moved.”

Lincoln shared the room with Speed for the next three-and-a-half years, often with other store clerks and assistants. One such clerk was a very young William Herndon, who later went into partnership with Lincoln. The atmosphere was jovial, and Lincoln was his usual story-telling self. Speed became Lincoln’s closest friend and confidant for the rest of his life, even though Speed eventually returned to his slave-holding family in Kentucky. As was common between men of those days, the two shared their most intimate vulnerabilities, a relationship that rivaled any of Lincoln’s romantic loves. When Speed questioned his affection for the woman he was about to marry, Lincoln helped him through the doubts. Later, when Lincoln was going through the same process, he turned to the happily married Speed for advice. He was seeking counsel regarding his relationship with Mary Todd.

On March 27, 1842, after an on-again, off-again courting of Mary Todd, Lincoln wrote to his friend, Joshua F. Speed, who had by that time moved back to his plantation in Louisville, Kentucky. Lincoln had abruptly broken off the engagement over a year before and it was eating at him.

“Since then, it seems to me, I should have been entirely happy, but for the never-absent idea, that there is one still unhappy whom I have contributed to make so. That still kills my soul. I can not but reproach myself, for even wishing to be happy while she is otherwise.”

Speed managed to counsel his old friend and sometime in 1842 Mary and Lincoln began secretly courting again. Despite her sister Elizabeth’s opposition, the two often met at the Edwards house and sat on the low couch for hours, talking about life and love. Likely they also discussed politics, as by this time Lincoln was actively involved in Whig party activities and Mary was as ambitious as he, perhaps even more so. Their romance bloomed again, enough that Mary flirtatiously and anonymously wrote a letter backing up Lincoln’s own anonymous letter to the local paper mocking James Shields, a political rival. Shields, feeling his honor had been attacked, challenged Lincoln to a duel. Lincoln tried to back out of it, but when Shields insisted, the tall and muscular Lincoln offered up heavy broadswords as weapon of choice. Faced with a severe disadvantage, the short-armed Shields allowed himself to be talked out of the fight.

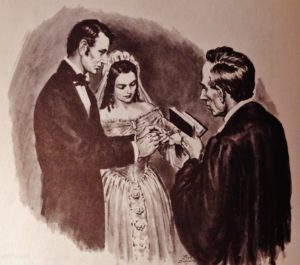

To the astonishment of the Springfield social set, Lincoln and Mary suddenly decided they would get married—that night. Elizabeth Edwards claimed the wedding occurred with only two hours’ notice, and indeed the marriage license was issued that very day. Lincoln had a “deer in the highlights” look as he approached the hurried ceremony in the Edwards parlor. According to friends, when Lincoln was dressing for ceremony he was asked where he was going, to which he replied, “I guess I’m going to hell.” At least one Lincoln scholar believes Mary may have seduced Lincoln the night before into doing something that obligated him to marriage. Whatever the reason, they were married on November 4, 1842. A week later he seemed resigned to the fact, closing a business letter with:

“Nothing new here except my marrying, which to me, is matter of profound wonder.”

[Adapted from Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America]

[Photo Credit: Photo of print by Lloyd Ostendorf]

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity (2013) and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World (2016) and two e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

Pingback: A Busy Day in Abraham Lincoln’s Life – David J. Kent