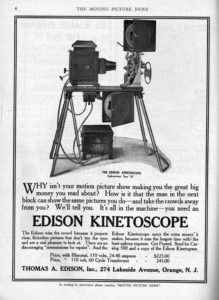

On August 31, 1897, Thomas Edison invented the movies. Or at least that was the day he patented the kinetoscope, an early motion picture projector. But as with all inventions, the story is much more complicated than just one man.

On August 31, 1897, Thomas Edison invented the movies. Or at least that was the day he patented the kinetoscope, an early motion picture projector. But as with all inventions, the story is much more complicated than just one man.

In fact, others had already started the process that Edison’s team would move forward. In June 1889, William Friese-Greene had patented a motion picture camera in England. Two months later, Englishman Wordsworth Donisthorpe patented his own version of a motion picture camera. Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince, a Frenchman working in England, developed a multiple-lens camera in 1888. Le Prince also filmed two motion picture sequences using a single-lens camera and paper film; the twelve-frame-per-second Roundhay Garden Scene runs for a grand total of 2.11 seconds. In a bizarre twist reminiscent of future action movies, Le Prince and his luggage mysteriously vanished from a moving train just prior to making a trip to the United States to present his invention.

These early inventors did not have the finances to continue development, but Edison did. The first version out of the Edison laboratory was “rather too ambitious,” as it attempted to synchronize the sound of the phonograph with the movement of images. “Thousands of tiny images” were taken with a conventional camera, and one by one they were mounted on a modified phonograph cylinder. A second cylinder played back the sound, ideally in sync with the images. But the machine did not work. The curvature of the cylinder distorted the small images, so it was nearly impossible to view them with any resolution. Increasing the size of the images to 1/4 inch and applying a photographic emulsion to the cylinder failed to resolve the problem, although Edison did produce a series of short films (of a few seconds each) collectively called Monkeyshines. Overall, however, the idea of using cylinders was abandoned.

Another Englishman, Eadweard Muybridge, came to the rescue. Muybridge was a photographer who as far back as the 1870s was producing images in series, which he used mainly to study the motion of animals. In one sequence, Muybridge had taken twelve rapid photos of a horse in full gallop in order to determine if all four legs were off the ground at the same time (they were). He accomplished this by using multiple cameras to record images in rapid succession.

Muybridge had also invented a zoopraxiscope, a rotating glass wheel and a slotted disk that projected a series of pictures in sequence, each slightly ahead of the other. Turning the wheel made the pictures appear to be in motion. With these devices in hand, the now-famous Muybridge paid a visit to Edison during a tour of the United States in February 1888. As with his earlier visit with Wallace, Edison gained considerable insights into his next steps after this meeting. Edison barely acknowledged the visit for months, but in October suddenly submitted his caveat to the patent office for “a system of motion pictures: a device to record the images, a device for viewing them, and an instrument that merged viewing pictures and listening to sound in the same experience.”

Étienne-Jules Marey was another influence on Edison’s thinking about motion pictures. After growing up in the Côte-d’Or region of France, Marey studied medicine and became interested in the science of laboratory photography; he is widely credited with being the Father of Chronophotography, or photographing motion. In 1882 he invented the chronophotographic gun, a menacing-looking instrument capable of capturing images at a rate of twelve frames per second. All twelve sequential still images were recorded on the same strip of film, a disk that rotated as the rapid-fire photos were taken. Marey also designed a camera that captured “sixty images a second on a long continuous strip of film, which was pulled by a cam in a deliberately jerky fashion to stop the film momentarily, so that the light could saturate the film and capture motion.” Edison sought out Marey when he attended the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris.

The World’s Fair’s biggest attraction was the huge iron-latticed tower named after its designer, Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, on whose edifice Edison wined and dined with the rich and famous during the exposition. But what really caught Edison’s interest was Marey’s photographic gun. Marey was more focused on the technical developments of his invention and less about the market value, and he gladly showed Edison the mechanics and examples of his work. He also gave Edison a copy of his book providing all the technical details. Armed with new ideas, but still lacking in substantive time to develop them, Edison passed the information to Dickson and left him to make something of it.

The Kinetoscope Emerges

Edison’s patent caveat was filed with Dickson working anonymously in the background. The device they had in mind would not only show pictures in motion, it would do so “in such a form as to be both Cheap[,] practical and convenient. This apparatus I call a Kinetoscope ‘Moving View.’”(The name is derived from the Greek kinesis, meaning motion.) They described it as a silver emulsion-coated phonograph cylinder with 42,000 “pin-point” photographic images each 1/32 inch wide mounted spirally upon it, to be viewed through a binocular eyepiece salvaged from a microscope; the visual cylinder spun to the simultaneous accompaniment of a contiguous phonograph sharing the same shaft and playing the “sound track.” The idea of synchronized cylinders was completely unworkable, but it epitomizes how Edison worked—he built on something he already did, and he hesitated to move away from it.

But move away he did. Dickson searched for a way to take and display the thousands of pictures that would need to be strung together for any length of viewing time. The usual way of making photographs was to produce them on glass negatives, which clearly was not an option for moving pictures. One option that seemed viable was celluloid, a plastic material made out of cellulose nitrate that English photographer John Carbutt successfully used. Another promising option was rolls of paper that George Eastman had managed to coat with photographic film and fused into a cheap Kodak camera.

Dickson experimented with celluloid and paper, and after Edison’s visit with Marey filed a new patent caveat, this one describing a “sensitive film” that would “pass from one reel to another.” Then, like the phonograph before it, the kinetoscope project was dropped—this time for only a year—while Edison kept Dickson busy with his ore milling business. When Dickson was finally allowed to return to the kinetoscope, Edison assigned William Heise to give him a hand.

Heise had expertise stemming from his prior work with printing telegraphs, which he now used to design the mechanical movement of film through the camera. Dickson focused on the optical components of the camera itself, along with the chemical and physical characteristics of the film. Together they developed the two parts that would make it possible to film, and then display, motion pictures.

By the spring of 1891, the two men had designed a camera, which they called a kinetograph, to film moving pictures. The kinetograph’s horizontal-feed exposed images on strips of perforated film 3/4 inch wide. A “shutter and escapement mechanism” allowed the camera to stop the film “for a fraction of a second,” just long enough to expose the film before advancing to the next exposure. Dickson and Heise advanced the technology with amazing rapidity: “forty-six impressions are taken each second, which is 2,760 a minute and 165,600 an hour.” Several short experimental films were produced, “including a lab worker smoking a pipe and another swinging a set of Indian clubs.”

After developing a suitable camera to create motion pictures, they needed to develop a way to watch them. The answer was a wooden box, much like those housing phonographs, which they called a kinetoscope. The box stood about four feet high and was twenty inches square. Inside the box was “an electric lamp, a battery-powered motor, and a fifty-foot ribbon of positive celluloid film arranged on a series of rollers and pulleys.” The film viewer would bend over the box, stare through an eyepiece, and watch as the film whizzed through view at forty-six frames per second.

And whiz it did. The first films were over in twenty seconds or less; basic scenes such as Dickson tipping his hat or a blacksmith banging his hammer. Still, it was a start, and Dickson continued to work on perfecting both the kinetograph camera and the kinetoscope player. Edison, on the other hand, was not sure there was much of a market: “This invention will not have any particular commercial value. It will be rather of a sentimental worth,” something of a novelty. At the same time he seemed to recognize the future attraction to the new medium, which could reproduce on the walls of their homes actors and scenes they currently had to go out to the theater to experience. Despite his hesitations, Edison arranged for a kinetoscope exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair. It was a couple of years in the future, so he had plenty of time to perfect the device. Or so he thought. He assigned James Egan, one of his machinists, to build twenty-five kinetoscopes.

Enter the Black Maria. Edison became a movie mogul.

[Adapted from Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World]

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

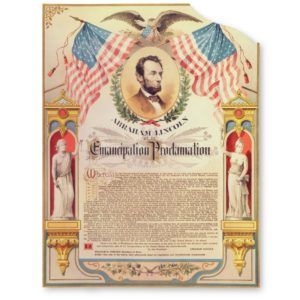

On August 26, 1863, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to James C. Conkling, his friend and political colleague in Springfield, explaining why the Emancipation Proclamation was necessary. In it he reveals the thought processes he went through to reach his decision. It was a much longer process than most people understood.

On August 26, 1863, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to James C. Conkling, his friend and political colleague in Springfield, explaining why the Emancipation Proclamation was necessary. In it he reveals the thought processes he went through to reach his decision. It was a much longer process than most people understood. Abraham Lincoln didn’t see much slavery as a small child growing up in northern Kentucky, or through his formative years in Indiana. But he did get an introduction of sorts.

Abraham Lincoln didn’t see much slavery as a small child growing up in northern Kentucky, or through his formative years in Indiana. But he did get an introduction of sorts. “Many a deluded inventor has spent years of his life in endeavoring to harness the tides.” – Nikola Tesla

“Many a deluded inventor has spent years of his life in endeavoring to harness the tides.” – Nikola Tesla