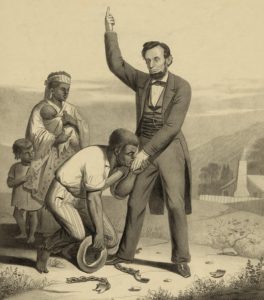

Abraham Lincoln didn’t see much slavery as a small child growing up in northern Kentucky, or through his formative years in Indiana. But he did get an introduction of sorts.

Abraham Lincoln didn’t see much slavery as a small child growing up in northern Kentucky, or through his formative years in Indiana. But he did get an introduction of sorts.

First, the church that his family belonged to in Kentucky began splitting off into northern (anti-slavery) and southern (pro-slavery) factions. Lincoln’s father Thomas followed the anti-slavery group and then moved into the free state of Indiana. When he was nineteen years old Lincoln made his first of two flatboat trips down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where he encountered his first slave markets and was attacked by escaping slaves. But largely he had little contact with slavery until adulthood.

While still living in New Salem, Lincoln was elected to the first of four terms in the Illinois state legislature. Most of his time was focused on economic issues such as internal improvements but the slavery issue did play one important role. As I wrote in my book, Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America.

Although the Illinois constitution banned slavery, it did have highly restrictive “black laws” that effectively limited the ability of free blacks to live and work in the state. At the same time, abolitionists who wanted a nationwide ban on slavery were gaining strength and influence. This led pro-slavery forces to push for anti-abolition resolutions. While Lincoln abhorred slavery—he later said, “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong”—he also felt the abolitionists were doing more harm than good. When the Illinois legislature passed an anti-abolitionist resolution, Lincoln was one of only six house members to vote against it. To clarify this seemingly counterintuitive position, he later wrote a protest, co-signed by Dan Stone, one of the Long Nine who was not seeking reelection. In the protest, the two men made clear they believed:

… that the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy; but that the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its evils.

And further, he said they believed:

… that the Congress of the United States has no power, under the constitution, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the different States.

Lincoln wanted everyone to understand he was anti-slavery, but also felt bound by the Constitutional restrictions on taking action against the “peculiar institution.” These were fairly radical thoughts for a young western legislator, and would set the stage for Lincoln to become a national leader on the issue of slavery.

Lincoln knew that slavery was tacitly acknowledged in the Constitution by its “three-fifths rule” and “fugitive slave clause.” He also knew that the framers of the Constitution had believed slavery would eventually go away. They took steps to help that process by passing the Northwest Ordinance (banning slavery in territories that became Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin) and, as soon as possible, banning the international slave trade. For most of his early career, Lincoln also believed that slavery would eventually disappear (“founded on injustice and bad policy”). Unfortunately, the invention of the cotton gin and vast expansion of the U.S. territories through the Louisiana Purchase and Mexican War had the opposite effect. Rather than dying away, slavery was threatening to expand into all the western territories and even the free northern states.

Something had to be done. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, pushed through Congress by Lincoln’s rival Stephen A. Douglas, “aroused him as he never had been before.” It was time for Lincoln to get back into politics.

[Adapted and expanded from my book, Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America.]

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

Fascinating – absolutely fascinating. Will get these in the near future – those books that I do not yet have.

Thanks, Kathryn. Lincoln is such an interesting guy to study.

Way back in my college days, I recall a professor suggesting that at least some of what affected Lincoln’s views on slavery had to do with his father periodically selling him into indentured servitude to others’ farms. Apparently a common practice among farmers in that time/place, shifting the work potential of children and teens when it wasn’t needed at home, that it nevertheless left Lincoln with a profound sense of injustice in the theft of one’s labors.

Argh. For the first time I didn’t copy the text and now it gave me an error and posted nothing of the very long response I prepared.

Trying again, shorter. Anyway, yes, Lincoln supposedly said “I used to be a slave” in the context of being farmed out by his father for labor. But whether he actually said it is debatable. The line comes from a recollection after the assassination from years earlier by someone who knew him. Fehrenbacher’s “Recollected Works” book gives it a “D” rating, which he defines as a quotation with “more than average doubt.”

And yes, it was common practice for fathers to hire out their sons (and daughters) to others, with all pay going back to the father until the son/daughter was 21 years old. Everyone did it. They had to. Often instead of pay they would either trade labor or get paid in food/product or other useful stuff.

I think most historians used the quote because it makes a good story, but others either don’t use it or put it into context. If it’s a legitimate quote, it could have been said for political expediency once Lincoln got deep into the national debate on slavery. Or he could have meant it (although I doubt it, since he would have known that it was the norm). In any case, he did focus on “the right to rise” for all men and felt slavery was an impediment to that happening.

Finally, he certainly felt that slavery was morally wrong and bad policy, and often said that everyone had the right to eat the bread resulting from their own labors. So yes, he had a profound sense of injustice and hated slavery, but he also saw how slavery held back both black and white laborers.

Ah, yes… I recognize both that spontaneous disappearance of unpreserved labors, as well as those ubiquitous quotations of dubious attribution.

That said, I appreciate such honestly critical preservation of history. I had just recently mentioned to someone impressed by a bit of Japanese history that it was something likely exaggerated, if not largely invented around one-hundred years ago. The motives of sources can sometimes be more revealing than their words.

I think it’s safe to say that after the assassination many who knew or saw Lincoln, even peripherally, made sure to comment about how close they were. A lot of stories seemed to reflect the storyteller’s exaggerations, if not outright fantasies. But still, most probably have some grain of truth and it’s great that we have so much information, especially of his life before becoming famous.