On September 27, 1841, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to Mary Speed, the half-sister of his good friend Joshua Speed. He spoke up about slavery, knowing that the Speed’s had been raised as slaveowners and having just returned from a long visit to their home in Kentucky. On the trip home he contemplates the inequities of life:

On September 27, 1841, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to Mary Speed, the half-sister of his good friend Joshua Speed. He spoke up about slavery, knowing that the Speed’s had been raised as slaveowners and having just returned from a long visit to their home in Kentucky. On the trip home he contemplates the inequities of life:

A gentleman had purchased twelve negroes in different parts of Kentucky and was taking them to a farm in the South. They were chained six and six together. A small iron clevis was around the left wrist of each, and this fastened to the main chain by a shorter one at a convenient distance from, the others; so that the negroes were strung together precisely like so many fish upon a trot-line. In this condition they were being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and many of them, from their wives and children, and going into perpetual slavery where the lash of the master is proverbially more ruthless and unrelenting than any other where; and yet amid all these distressing circumstances, as we would think them, they were the most cheerful and apparently happy creatures on board. One, whose offence for which he had been sold was an over-fondness for his wife, played the fiddle almost continually; and the others danced, sung, cracked jokes, and played various games with cards from day to day. How true it is that “God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb,” or in other words, that He renders the worst of human conditions tolerable, while He permits the best, to be nothing better than tolerable.

Lincoln loathed slavery as far back as the late 1830s, but he rarely spoke out about the slavery question until the 1850s. There were several reasons for his silence, starting with his belief that the institution was dying out. In a response to Stephen A. Douglas in June 1858, he told a Chicago audience that the Republican Party was made up of people “who will hope for its ultimate extinction.” How could it not be so, he thought, given that slavery is morally wrong and politically unsustainable?

This belief proved to be naïve. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 had made it possible to separate cotton fibers from its seeds mechanically; previously this painstaking process was performed entirely by hand and involved hundreds of hours of manual, usually slave, labor. Most northern states had banned slavery, but most southern states saw an expansion of slavery correlated with the growth of “King Cotton.” With the separation (ginning) process speeding the rate of production, plantation owners could dramatically increase the acreage on which they grew cotton. As cotton acreage expanded, more and more slaves were needed for cultivation. Rather than being on the cusp of extinction, slavery was booming.

Once he recognized this reality, Lincoln focused on how to stop its expansion. I talked about some of the ways, in particular his long road to emancipation of enslaved people in the District of Columbia, during my recent keynote address on Lincoln-Thomas Day at Fort Stevens in the District. I talked about other ways in my book, Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America. I’ll have more on this website in the future.

[Partially adapted from Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America]

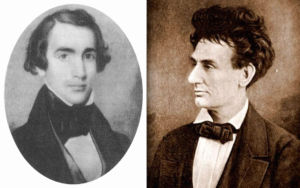

[Note: Photo is of Joshua Speed and Abraham Lincoln]

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

Anything between Lincoln and Speed is priceless.

Thank you for bringing this to our attention.

Still, i see this letter is from 1841. So while it’s interesting, to understand Lincoln,and the time (especially who killed who, and why, in blunt terms) we would need information what happened from 1846 -1861.

Not just leltters from Lincoln, but his full speeches, and even more importantly, from South leaders themselves bragging about it in surprisingly candid terms,. Later, after they lost, South leaders gave a drastically different narrative, but at the time, while they killed, while they sent the killers, they boasted of things that would shock most history teachers today, which is a shame. They should have been taught that more than taught the Gettysburg address and other things. The basis events of US history during this time was the killing and tortures done by paid men, hired by, Southern leaders who bragged about it.

The way we teach that is so watered down as to be useless. Our students are dumber from learning the watered down version, which teaches instead such nonsense as the cotton gin was a cause of the spread of slavery.

WE need not be unaware of what happened- – the South leaders bragged about it at the time, in writing, in speeches, and in their own proclamations and war ultimatums.

South leaders own actions and statements are crucial — and missing from our text books.

Slave power induced Polk to invade and murder enough Mexicans to spread slavery to several million more square miles, as was the goal of the war. If you don’t believe that, learn that Henry Clay and Alexander Stephens both essentially admitted that, and was widely known, and is what happened.

And of course Lincoln tried to stop that killing spree (we call it a war) for that very reason.

Plus, we’d need to know of Southern leaders own actions and boasting while invading KS in 1856, using men hired and led by the US Senator who passed Kansas Act, then rushed to Kansas to terrorize, later kill and boast of it, to spread slavery not just to Kansas Territory, but to spread it to the Pacific.

Lincoln of course knew all this exceedingly well, as his letter to Speed shows, and virtually everyone alive knew it at the time. Not just because South leaders admitted it at the time, in fact bragged about it. but because that is what happened, apart from their boasting of it

Do to justice to anyone at the time, including Lincoln, we need to learn who South leaders paid to kill who– and what they bragged about.

Sadly we do not teach such things in US class rooms, or text books. .

It is unequivocal that slavery was the cause of secession and the Civil War. Southern leaders stated this belief repeatedly in the antebellum decades as threats, and then as action after Lincoln was elected. All of the ordinances of secession from the slaveholding states stated explicitly that slavery was the reason for secession. Confederate VP Stephens explicitly defined “the superiority of the white race and inferiority of the black race” and the institution of slavery as the cornerstone of the new Confederacy. All of the slaveholding states’ actions in the decades leading up to the Civil War were directed at expanding the reach and political power of slaveholders, including the Mexican War of 1846-48, the Ostend Manifesto of 1854, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the Dred Scott Decision of 1857, and secession and Civil War.

Lincoln’s letters with people like Speed (Joshua and his sister Mary) are great sources of information on what Lincoln was thinking. There always seems to be something new to learn from them.