On January 25, 1865, Abraham Lincoln directed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to give Lincoln’s Jewish spy and “cheroperdist” a pass to go into southern territory.

On January 25, 1865, Abraham Lincoln directed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to give Lincoln’s Jewish spy and “cheroperdist” a pass to go into southern territory.

“I wish you to give Dr. Zacharie a pass to Savanna, remain a week and return, bringing with him, if he wishes, his father and sisters or any of them.”

So who is Dr. Zacharie, and what is a “cheroperdist”?

Let’s start with the second part. When the self-styled foot doctor Issachar Zacharie (he actually had no medical training and gave himself the “Dr.” honorific) first printed business cards to advertise his ability to relief sufferers from corns and bunions, he misspelled the word “chiropodist.” While possibly recognizable to many people today, the term chiropodist is outdated and synonymous with today’s term for foot doctor: podiatrist. Even though he didn’t have any official credentials, it turns out Dr. Zacharie was an excellent chiropodist and operated on Abraham Lincoln’s feet and those of many of his staff and officer corps. Zacharie serviced thousands of Union soldiers during the Civil War.

Just as Dr. Zacharie invented his profession and persona, he invented himself as a sort of Union spy. His exploits were extolled in a new book by E. Lawrence Abel called Lincoln’s Jewish Spy: The Life and Times of Issachar Zacharie. This is the short review I wrote on Goodreads:

An interesting in-depth look at a rarely examined public figure associated with Lincoln. Unafraid of self-promotion, even if he had to fabricate an educational background, Issachar Zacharie manages to insert himself into Abraham Lincoln’s inner circle. That is, at least to some extent as Abel tells us it’s sometimes difficult to separate Zacharie’s self-promotion from reality. Abel helps parse out that difference and shows us that Zacharie was in fact somewhat of an informant for Lincoln and a close associate of the ambitious, if not overly competent, General Nathaniel Banks. Along the way we learn much about being Jewish in nineteenth century America. Oh, and we also learn about chiropody, the cutting and shaving of foot corns and bunions (which turns out to have been a bigger problem for soldiers and politicians than could be imagined).

The depth of Abel’s research is readily apparent, as is the breadth of his sourcing. He manages to flesh out a little known character of the Civil War that is both interesting and informative. The book at times is repetitive and could have used some tighter editing in places, but overall is a great read for anyone interested in digging deeper into lesser known names.

Stanton replied to Lincoln’s directive the same day to note “An order for leave to Zacharie as directed by you has been issued & sent to Mr. Nicolay.” Zacharie apparently replied to say “I leave on Saturday per steamship Arago for Savannah where I hope to find my Dear old father and friends–if you have any matters that you would have properly attended to, I will consider it a favour to [you] to let me attend to it for you…”

Zacharie was quick to ingratiate himself with the Jewish population wherever he traveled. He would collect intelligence for the war effort, and also relay advice to Jewish men on how to help the Union effort. This is a little known element of the war and Abel’s book gives us much insight into that regard.

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Follow me for updates on my Facebook author page and Goodreads.

The election results were decisive. The new president-elect had won the popular vote by a substantial margin and had won more electoral votes than his competitors combined. The election had been secure, and the results were unequivocal.

The election results were decisive. The new president-elect had won the popular vote by a substantial margin and had won more electoral votes than his competitors combined. The election had been secure, and the results were unequivocal.

The recent pressure to remove Confederate statues has spilled over into monuments to other historical figures, most incredibly including

The recent pressure to remove Confederate statues has spilled over into monuments to other historical figures, most incredibly including

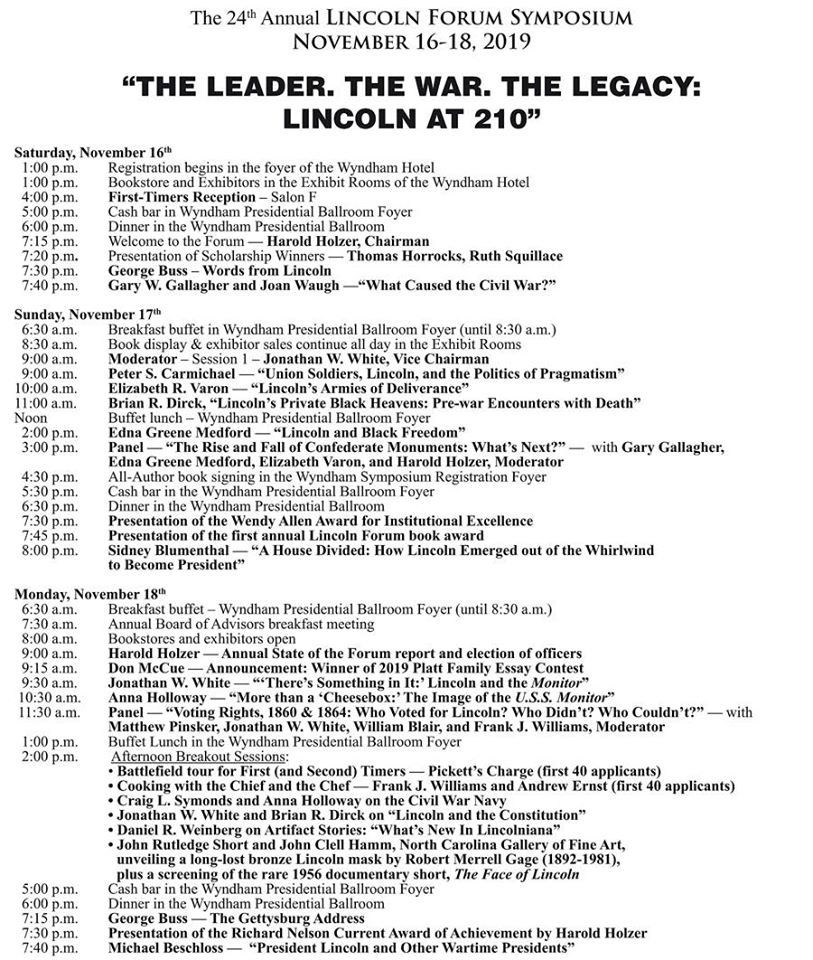

A funny thing happened on the way to the Lincoln Forum. After a career as a scientist, I became a Lincoln historian. And in a few days I’ll have the chance to join 300 of my colleagues at the annual Abraham Lincoln Forum.

A funny thing happened on the way to the Lincoln Forum. After a career as a scientist, I became a Lincoln historian. And in a few days I’ll have the chance to join 300 of my colleagues at the annual Abraham Lincoln Forum.