No one would mistake Abraham Lincoln for an artist, though scholars give him high marks on his writing. Long before there were speechwriters, politicians wrote their own material, and Lincoln is well known for such memorable speeches as the Gettysburg and Second Inaugural Addresses. He was also a great letter writer, often crafting policy positions in the form of “private” letters that were, in fact, intended for public consumption. His response to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, for example, in which he states his position on emancipation of the slaves, thus preparing the public for the proclamation that he had already prepared but not yet revealed, is a classic of historical writing.

No one would mistake Abraham Lincoln for an artist, though scholars give him high marks on his writing. Long before there were speechwriters, politicians wrote their own material, and Lincoln is well known for such memorable speeches as the Gettysburg and Second Inaugural Addresses. He was also a great letter writer, often crafting policy positions in the form of “private” letters that were, in fact, intended for public consumption. His response to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, for example, in which he states his position on emancipation of the slaves, thus preparing the public for the proclamation that he had already prepared but not yet revealed, is a classic of historical writing.

But did you know that our 16th President wrote poetry? Perhaps not on par with Robert Burns (one of his favorite poets), but clever and with great storytelling. Which reminds us that Lincoln is well known for his ability to tell a humorous story.

Nikola Tesla was also fond of poetry. He could recite long classic poems in their entirety, and could do so in several different languages. Tesla’s own writings were perhaps not as succinctly to the point as Lincoln’s but they were often entertaining and fanciful; not an easy task for an electrical engineer writing about cutting edge technical discoveries. Most of our knowledge of his childhood and early adult years come from Tesla’s own autobiographical accounts serialized in the scientific magazines of the day.

Tesla also was a big fan of the writings of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain. Which gets us to yet another connection between Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla.

Mark Twain in the House

Samuel Clemens, known to most of us by his pseudonym Mark Twain, was born in Hannibal, Missouri on November 30, 1835, shortly after Halley’s Comet had made its regular but rare pass by the Earth. The 26-year-old Abraham Lincoln – an amateur astronomy buff who two years earlier had marveled at the Leonid meteor showers – may very well have been gazing at the skies when Mark Twain came into this world. At that age Lincoln lived in New Salem, Illinois, just a stone’s throw across the Mississippi River from Hannibal. In 1859, Lincoln rode the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad to give a speech in Council Bluffs, Iowa. The railroad just happened to be formed in the office of Mark Twain’s father thirteen years before.

Lincoln floated flatboats down the Mississippi River to New Orleans as a young adult, then took steamboats back upriver. He often piloted steamboats around shoals near his New Salem home. Mark Twain had worked on steamboats on the river for much of his younger years, first as a deckhand and then as a pilot. Being a riverboat pilot gave him his pen name; “mark twain” is “the leadsman’s cry for a measured river depth of two fathoms (12 feet), which was safe water for a steamboat.” In 1883 Twain even titled his memoir, Life on the Mississippi. Lincoln’s time traveling on and piloting steamboats eventually inspired his patent for lifting boats over shoals and obstructions on the river.

Lincoln would not have read any of Mark Twain’s stories (his first, The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, was published in 1865, about seven months after Lincoln had been assassinated). But Twain says his humorous writing style was strongly influenced by another pen named-humorist, Artemus Ward, and the Jumping Frog story was published in the New York Saturday Press only because he finished it too late to be included in a book Artemus Ward was compiling. This is the same Artemus Ward that was so often read by Abraham Lincoln to break the tensions of the Civil War.

In fact, Lincoln was so entranced by the humor of Ward that on September 22, 1862 he read snippets from one of Ward’s books to his cabinet secretaries before settling into the business of the day – the first reading of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Ironically, Mark Twain’s piloting job ended when the Civil War started, as much of the Mississippi River became part of the war zone. So what is a writer/river-boatman to do? Well, join the Confederate army of course. His unpaid service lasted only two weeks in 1861 before disbanding. He then left for Nevada to work for his older brother, out of harm’s way for the rest of the war, though his brief service for the confederacy did give him material for another of his humorous sketches, The Private History of a Campaign That Failed.” Later, Mark Twain would publish the memoirs of Civil War hero and President, Ulysses S. Grant.

Like Lincoln, Mark Twain was very interested in science and technology. Twain actually had three patents of his own, for a type of alternative to suspenders, a history trivia game, and a self-pasting scrapbook. Many years after the Civil War he met and became close friends with Nikola Tesla. Often when he was in New York City Twain would hang out in Tesla’s laboratory. One photo taken only with the light produced by Tesla’s wireless lighting technology shows Mark Twain holding a ball of light.

They became such good friends that Tesla felt comfortable playing a practical joke on him. One day Mark Twain dropped by the lab and Tesla decided to have a little fun. He asked Twain to step onto a small platform and then set the thing vibrating with his oscillator. Twain was thrilled by the gentle sensations running through his body.

“This gives you vigor and vitality,” he exclaimed.

After a short time Tesla warned Twain that he better come down now or risk the consequences.

“Not by a jugfull,” insisted Twain, “I am enjoying myself.”

Continuing to extol on the wonderful feeling for several more minutes Twain suddenly stopped talking. Looking pleadingly at Tesla he yelled:

“Quick, Tesla! Where is it?”

“Right over there,” Tesla responded calmly. Off Twain rushed to the restroom, embarrassed by his suddenly urgent condition. Tesla smiled; the laxative effect of the vibrating platform was well known to the chuckling laboratory staff.

By the way, Mark Twain was also friends with Thomas Edison. And Edison filmed the only footage of Mark Twain currently in existence. The less-than-two-minute-long film would not win any Academy Awards for content or production value – its grainy images show Twain merely walking while smoking his cigar and eating lunch with his two daughters – but it has obvious cultural and historical significance. Mark Twain died the following year, the day after Halley’s Comet returned for the first time since Twain’s birth, in effect, seeing him both into this world and out of it.

[The above is adapted from my e-book, Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate, available for download on Amazon.com.]

Click here for more posts here on Science Traveler about the connections between Lincoln and Tesla.

David J. Kent is the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, now available. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World (both Fall River Press). He has also written two e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

Follow me by subscribing by email on the home page. Share with your friends using the buttons below.

[Daily Post]

Like this:

Like Loading...

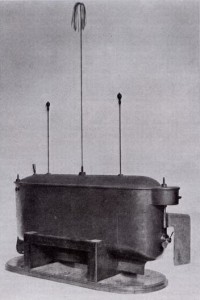

People today are fascinated by artificial intelligence and robotics. But did you know that Nikola Tesla was the first to demonstrate robotics in 1898? He enthralled onlookers with his robot boat in New York City long before Isaac Asimov made robots chic.

People today are fascinated by artificial intelligence and robotics. But did you know that Nikola Tesla was the first to demonstrate robotics in 1898? He enthralled onlookers with his robot boat in New York City long before Isaac Asimov made robots chic.

Nikola Tesla believed that the thermo-dynamic process, i.e., the burning of fossil fuels, was “wasteful and barbarous.” In particular he singled out coal; at the time in greater use than natural gas and oil, which were slightly less dirty but rapidly extending in use. Despite these

Nikola Tesla believed that the thermo-dynamic process, i.e., the burning of fossil fuels, was “wasteful and barbarous.” In particular he singled out coal; at the time in greater use than natural gas and oil, which were slightly less dirty but rapidly extending in use. Despite these

I’m happy to say that I’ve played a small role in bringing more recognition to the man. My book,

I’m happy to say that I’ve played a small role in bringing more recognition to the man. My book,  Rotating magnetic fields, alternating current motors and transformers, the Tesla coil, wireless transmission of radio communication, wireless lighting…Nikola Tesla had no shortage of inventions that he could call his own. But these were not the only inventions in which he dabbled. Besides his wireless radio communication and alternating current systems, and like other great inventors from da Vinci to Edison, Tesla was intrigued by a great many other issues. One such issue to which he gave a great deal of thought was the relationship between matter and energy. Late in life he even claimed to have developed a new dynamic

Rotating magnetic fields, alternating current motors and transformers, the Tesla coil, wireless transmission of radio communication, wireless lighting…Nikola Tesla had no shortage of inventions that he could call his own. But these were not the only inventions in which he dabbled. Besides his wireless radio communication and alternating current systems, and like other great inventors from da Vinci to Edison, Tesla was intrigued by a great many other issues. One such issue to which he gave a great deal of thought was the relationship between matter and energy. Late in life he even claimed to have developed a new dynamic  Einstein, of course, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 “for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.” While he is probably best known for his development of “the world’s most famous equation, E = mc2,” Einstein’s greatest contributions were in reconciling the laws of classical mechanics with the laws of electromagnetic fields. He believed that Newtonian mechanics did not adequately accomplish this reconciliation, which led to his special theory of relativity in 1905. Extending this concept to gravitational fields, Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1916. The following year he applied the general theory to model the structure of the universe as a whole.

Einstein, of course, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 “for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.” While he is probably best known for his development of “the world’s most famous equation, E = mc2,” Einstein’s greatest contributions were in reconciling the laws of classical mechanics with the laws of electromagnetic fields. He believed that Newtonian mechanics did not adequately accomplish this reconciliation, which led to his special theory of relativity in 1905. Extending this concept to gravitational fields, Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1916. The following year he applied the general theory to model the structure of the universe as a whole.

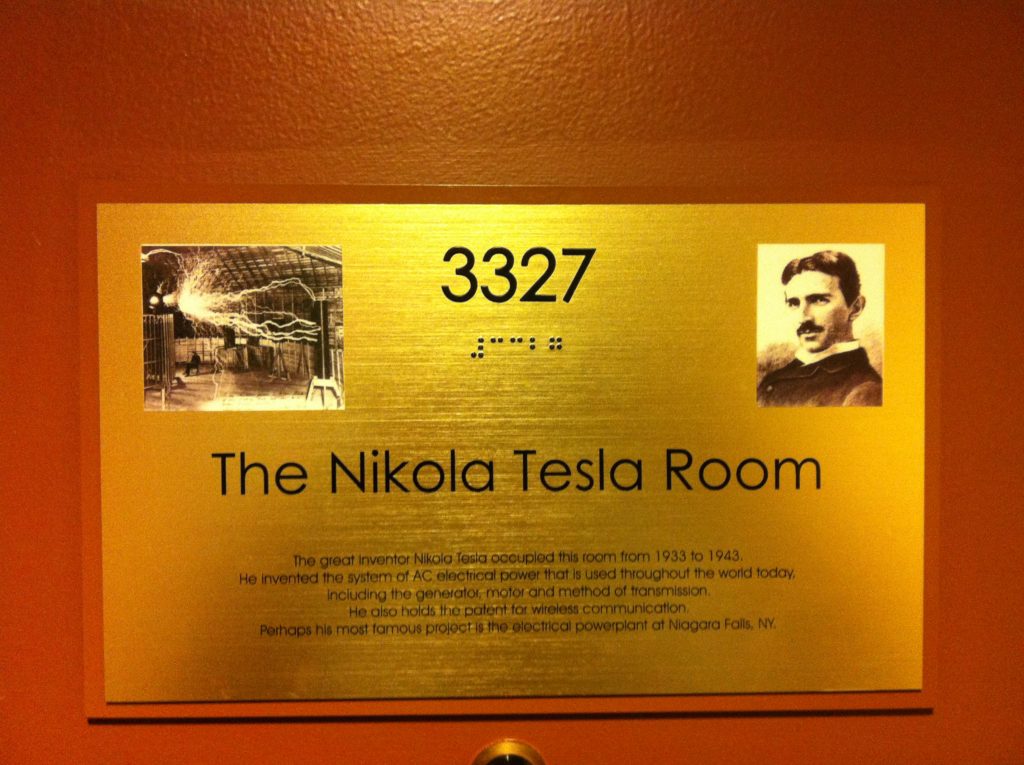

Nikola Tesla was an eccentric genius that was born just before the U.S. Civil War and died in the middle of World War II. Since its release, my book, Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity, has been a big reason nearly 100,000 new people have learned about him. And now there is even bigger news.

Nikola Tesla was an eccentric genius that was born just before the U.S. Civil War and died in the middle of World War II. Since its release, my book, Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity, has been a big reason nearly 100,000 new people have learned about him. And now there is even bigger news. One of the most important events of Nikola Tesla’s youth relates to Tesla’s childhood cat Mačak. As Tesla writes in a letter to a friend’s daughter, at one point during a cold snowy day Tesla “felt impelled to stroke Mačak’s back.” He notes that what he saw “was a miracle which made me speechless…Mačak’s back was a sheet of light, and my hand produced a shower of crackling sparks loud enough to be heard all over the place.” Tesla’s father explained that this must be caused by electricity, like that of lightning, and this thought convinced Tesla that he wanted to pursue becoming an “electrician.”

One of the most important events of Nikola Tesla’s youth relates to Tesla’s childhood cat Mačak. As Tesla writes in a letter to a friend’s daughter, at one point during a cold snowy day Tesla “felt impelled to stroke Mačak’s back.” He notes that what he saw “was a miracle which made me speechless…Mačak’s back was a sheet of light, and my hand produced a shower of crackling sparks loud enough to be heard all over the place.” Tesla’s father explained that this must be caused by electricity, like that of lightning, and this thought convinced Tesla that he wanted to pursue becoming an “electrician.” Nikola Tesla was one of the most famous inventors of his age, and then he was mostly forgotten, dying in near poverty. In recent years Tesla has seen a resurgence in popularity as Tesla Motors has brought the Serbian-American inventor back into the limelight. [And perhaps my book, Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity, has played a small role in spreading the Tesla word to the masses.]

Nikola Tesla was one of the most famous inventors of his age, and then he was mostly forgotten, dying in near poverty. In recent years Tesla has seen a resurgence in popularity as Tesla Motors has brought the Serbian-American inventor back into the limelight. [And perhaps my book, Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity, has played a small role in spreading the Tesla word to the masses.]

No one would mistake Abraham Lincoln for an artist, though scholars give him high marks on his writing. Long before there were speechwriters, politicians wrote their own material, and Lincoln is well known for such memorable speeches as the Gettysburg and Second Inaugural Addresses. He was also a great letter writer, often crafting policy positions in the form of “private” letters that were, in fact, intended for public consumption. His response to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, for example, in which he states his position on emancipation of the slaves, thus preparing the public for the proclamation that he had already prepared but not yet revealed, is a classic of historical writing.

No one would mistake Abraham Lincoln for an artist, though scholars give him high marks on his writing. Long before there were speechwriters, politicians wrote their own material, and Lincoln is well known for such memorable speeches as the Gettysburg and Second Inaugural Addresses. He was also a great letter writer, often crafting policy positions in the form of “private” letters that were, in fact, intended for public consumption. His response to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, for example, in which he states his position on emancipation of the slaves, thus preparing the public for the proclamation that he had already prepared but not yet revealed, is a classic of historical writing.