On August 26, 1863, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to James C. Conkling, his friend and political colleague in Springfield, explaining why the Emancipation Proclamation was necessary. In it he reveals the thought processes he went through to reach his decision. It was a much longer process than most people understood.

On August 26, 1863, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to James C. Conkling, his friend and political colleague in Springfield, explaining why the Emancipation Proclamation was necessary. In it he reveals the thought processes he went through to reach his decision. It was a much longer process than most people understood.

In fact, by the early spring of 1862, Lincoln had privately decided to issue an emancipation order. He kept this decision to himself for many months while secretly drafting his arguments. Meanwhile, he publicly voiced apprehension about such a decision, suggesting that turning the rationale of the war from maintaining the Union to freeing the slaves would cause significant loss of northern support, in addition to creating potentially disastrous implications in the border states.

In April 1862, at Lincoln’s urging, Congress emancipated slaves in the District of Columbia and compensated their owners. That June, Lincoln signed a bill prohibiting slavery in all current and future U.S. territories. Most of these steps went largely unnoticed to anyone not directly affected, but they helped move public sentiment toward freedom. Unbeknownst to anyone, Lincoln was preparing a draft of the now-famous document as he shuttled between the Soldier’s Home where he spent his summers and the telegraph office of the War Department. After some surreptitious lobbying of public opinion over the summer, Lincoln finally released his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. Written in dry, legal language, the proclamation stipulates that on:

…the first day of January [1863], all persons held as slaves within any state, or designated part of a state, the people shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free…

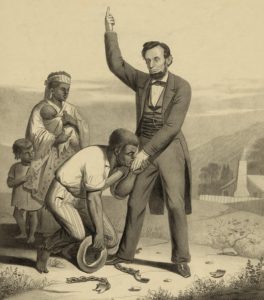

The initial reaction was as Lincoln expected. Many of the more radical Republicans were ecstatic, while Democrats and other “peace at all costs” proponents saw it as an unnecessarily extreme act. Many voters agreed; Republicans lost twenty-eight seats in the House of Representatives that November. As Lincoln feared, many northerners were vehemently opposed to a civil war to free the slaves as opposed to preserve the Union. Despite these losses, Lincoln stood by his decision and signed the final Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

Nearly a year later there was still grumbling in the North about the emancipation order. In August 1863, James Conkling invited Lincoln out to Illinois to explain to supporters why he proclaimed slaves free, some questioning whether it was right to do so. Many were worried that the public would not support the idea of fighting for “negro freedom.”

In his reply letter, Lincoln says his wartime duties precluded travel to Illinois, but explained to Conkling why he believed the Emancipation Proclamation was right. He noted their concerns, but reminded them that many African-Americans, both former slave and freemen, had joined the Union army and navy. He also suggested that Union forces and the public sentiment should continue fight to save the Union irrespective of their views on freeing the enslaved population.

You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then, exclusively to save the Union. I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union. Whenever you shall have conquered all resistance to the Union, if I shall urge you to continue fighting, it will be an apt time, then, for you to declare you will not fight to free negroes.

Near the end of his letter he again reminded white Northerners that the emancipation of enslaved people and the saving of the Union were intertwined, that one assured the other. He also reminded them that all men, black and white, had made sacrifices to maintain the Union, as well as have a Union worth maintaining. Victory was in sight.

Peace does not appear so distant as it did. I hope it will come soon, and come to stay; and so come as to be worth the keeping in all future time. It will then have been proved that, among free men, there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet; and that they who take such appeal are sure to lose their case, and pay the cost. And then, there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it.

As with his earlier letter to Horace Greeley, Lincoln intended and knew that his letter to Conkling would be reprinted in the nation’s newspapers, thus ensure wide distribution of his policy explanation. This was one mechanism by which Lincoln both heeded public sentiment and helped influence it. [He also had John Hay and John Nicolay ghostwriting editorials, but that’s a topic for another post.]

Lincoln wasn’t finished, of course. He understood that the Emancipation Proclamation was a war measure but a more permanent solution was necessary once hostilities ended. Lincoln then set on both winning the war and pushing for what became the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, banning slavery and making all men and women “thenceforward, and forever free.”

[Adapted in part and expanded from my book, Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America.]

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

Abraham Lincoln didn’t see much slavery as a small child growing up in northern Kentucky, or through his formative years in Indiana. But he did get an introduction of sorts.

Abraham Lincoln didn’t see much slavery as a small child growing up in northern Kentucky, or through his formative years in Indiana. But he did get an introduction of sorts. Last week I had the privilege of visiting with the

Last week I had the privilege of visiting with the

On April 4, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln took his son Tad into the city of Richmond, Virginia. The city had fallen the day before into Union hands two days before. It was Tad’s 12th birthday.

On April 4, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln took his son Tad into the city of Richmond, Virginia. The city had fallen the day before into Union hands two days before. It was Tad’s 12th birthday.

After an unfortunate breakup with a woman named Mary Owens, and with negotiations over moving the capital from Vandalia to Springfield under way, Abraham Lincoln decided to leave New Salem for the big city. The move was advantageous.

After an unfortunate breakup with a woman named Mary Owens, and with negotiations over moving the capital from Vandalia to Springfield under way, Abraham Lincoln decided to leave New Salem for the big city. The move was advantageous. an article published in

an article published in

Most people of heard of Doris Kearns Goodwin from her bestselling book, Team of Rivals, about Abraham Lincoln picking many of his political rivals to key cabinet positions. Initially well sold, it got a huge boost after then-candidate Barack Obama was seen carrying it on the campaign trail prior to his 2008 election, then again when Obama picked his rival Hillary Clinton to be Secretary of State, much like Lincoln put William Seward in that position. Another boost came from Steven Spielberg’s movie, Lincoln, which was based on a tiny part of Goodwin’s book.

Most people of heard of Doris Kearns Goodwin from her bestselling book, Team of Rivals, about Abraham Lincoln picking many of his political rivals to key cabinet positions. Initially well sold, it got a huge boost after then-candidate Barack Obama was seen carrying it on the campaign trail prior to his 2008 election, then again when Obama picked his rival Hillary Clinton to be Secretary of State, much like Lincoln put William Seward in that position. Another boost came from Steven Spielberg’s movie, Lincoln, which was based on a tiny part of Goodwin’s book.

The year 2018 in a writer’s life was good. Well, kind of up and down, really. Okay, let’s just call it a year of transition. And that is actually a good thing.

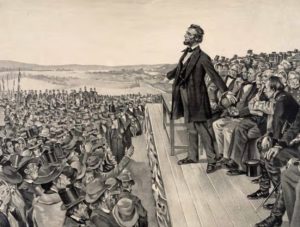

The year 2018 in a writer’s life was good. Well, kind of up and down, really. Okay, let’s just call it a year of transition. And that is actually a good thing. Union victories were coming more frequently in the late summer and fall of 1863, although not universally, as a loss at Chickamauga and the New York draft riots would attest. But now it was time for a more somber occasion.

Union victories were coming more frequently in the late summer and fall of 1863, although not universally, as a loss at Chickamauga and the New York draft riots would attest. But now it was time for a more somber occasion. But wait, there’s more. This past year I made several “Chasing Abraham Lincoln” trips, including long road trips to Kentucky/Indiana and Illinois. Check out my

But wait, there’s more. This past year I made several “Chasing Abraham Lincoln” trips, including long road trips to Kentucky/Indiana and Illinois. Check out my  Abraham Lincoln was the Whig candidate in 1846 and, as per a gentlemen’s agreement with other Whigs, served one term as a U.S. Congressman from December 1847 to March 1849.

Abraham Lincoln was the Whig candidate in 1846 and, as per a gentlemen’s agreement with other Whigs, served one term as a U.S. Congressman from December 1847 to March 1849.