I’m currently chasing Abraham Lincoln’s wigwam, the name given to the building in which Lincoln received the Republican nomination for President in 1860. Here’s the backstory:

I’m currently chasing Abraham Lincoln’s wigwam, the name given to the building in which Lincoln received the Republican nomination for President in 1860. Here’s the backstory:

Lincoln’s preparation for the Republican National Convention actually began in the fall of 1859, with old friend Norman Judd serving on the committee to decide when and where to have the assembly. Each of the main contenders for the nomination wanted a site that best benefitted him: New York’s William Seward wanted New York City, Ohioan Salmon P. Chase wanted Cleveland, and Missouri’s Edward Bates wanted St. Louis. Judd suggested Chicago. After all, he explained, there was no prominent candidate from Illinois, so Chicago would be a neutral site. The committee agreed to have the convention in Chicago, demonstrating how little they considered Lincoln a viable candidate.

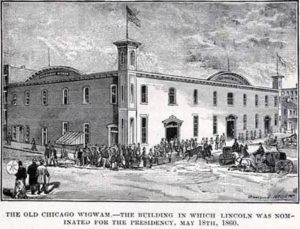

There was one problem: Chicago did not have a building big enough to handle all the delegates, so the national committee allocated funds for building a suitable temporary space. In a credit to engineering, the hastily erected convention hall—nicknamed the Wigwam—provided seating space for more than 10,000 delegates and observers, all with good views of the speaker’s platform and excellent acoustics.

As was the custom, Lincoln stayed at home in Springfield while David Davis and a cadre of others who knew Lincoln from the Eighth Judicial Circuit took the train to Chicago. Their strategy was to stop the default support for William Seward, then line up around 100 delegates willing to vote for Lincoln on the first ballot, make sure he gained votes on the second ballot, and win the nomination on the third ballot. For two days before the voting began, Davis and his colleagues talked with delegations from Indiana, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Massachusetts to encourage them to fall to Lincoln if their preferred candidate failed to get enough support. Lincoln’s team was coached to talk about Lincoln’s life, character, and great ability. They were instructed to always commend Seward in the highest terms, but point out that he would have difficulty winning the swing states. In stark contrast, Thurlow Weed and other Seward men put on airs of inevitability and put off delegates by telling everyone Lincoln was “greatly the inferior.”

In a letter to Samuel Galloway, Lincoln instructed his campaign committee to consider:

My name is new in the field; and I suppose I am not the first choice of a very great many. Our policy, then, is to give no offence to others—leave them in a mood to come to us, if they shall be compelled to give up their first love.

The strategy worked. As expected, Seward received 173.5 votes on the first ballot. Lincoln surprised many by receiving 102, while Cameron, Chase, and Bates attracting only around 50 apiece. On the second ballot, Seward picked up a few votes to 184.5 while Lincoln surged up to 181 as he siphoned votes from the others. After the third ballot Lincoln took the lead with 231.5 out of the 233 needed, with Seward decreasing slightly to 180 and the others falling completely out of contention. Seeing how close Lincoln was, the Ohio delegation switched four votes to give Lincoln enough for the win, further supplemented by a huge wave of changed votes to total 364. Abraham Lincoln was the Republican nominee for President. Hannibal Hamlin of Maine was selected by the delegations as Lincoln’s running mate.

[Adapted from Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America. I’ll soon be in Chicago seeking the new stone and plaques marking the location of the Wigwam.]

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!