On September 27, 1841, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to Mary Speed, the half-sister of his good friend Joshua Speed. He spoke up about slavery, knowing that the Speed’s had been raised as slaveowners and having just returned from a long visit to their home in Kentucky. On the trip home he contemplates the inequities of life:

On September 27, 1841, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to Mary Speed, the half-sister of his good friend Joshua Speed. He spoke up about slavery, knowing that the Speed’s had been raised as slaveowners and having just returned from a long visit to their home in Kentucky. On the trip home he contemplates the inequities of life:

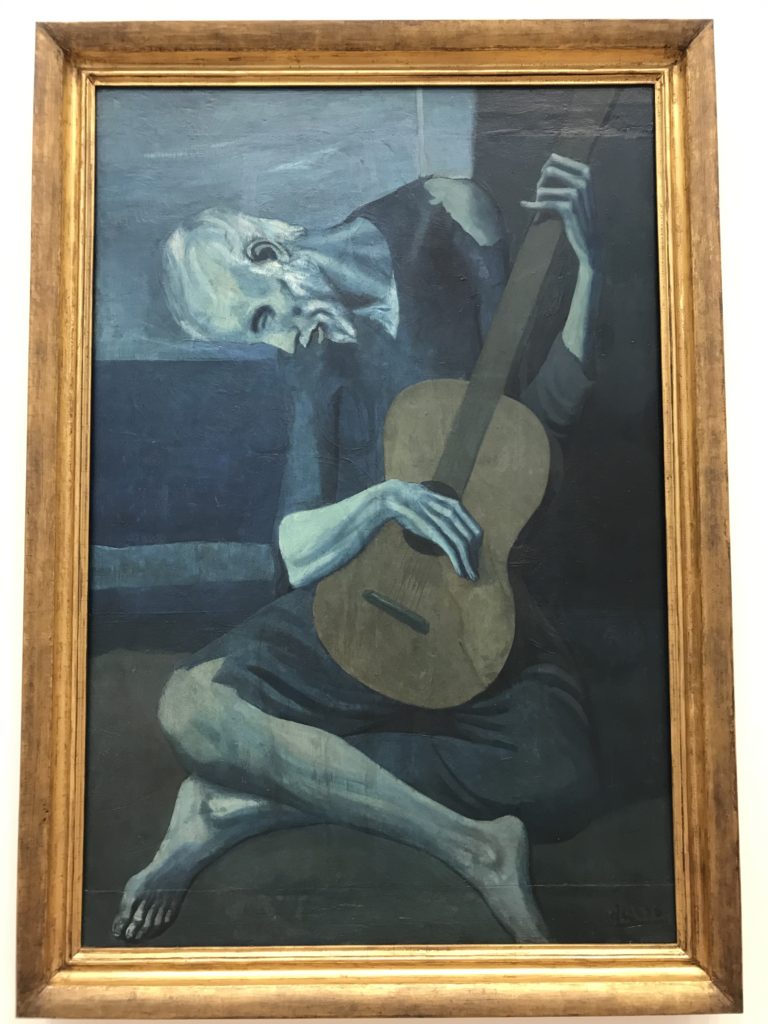

A gentleman had purchased twelve negroes in different parts of Kentucky and was taking them to a farm in the South. They were chained six and six together. A small iron clevis was around the left wrist of each, and this fastened to the main chain by a shorter one at a convenient distance from, the others; so that the negroes were strung together precisely like so many fish upon a trot-line. In this condition they were being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and many of them, from their wives and children, and going into perpetual slavery where the lash of the master is proverbially more ruthless and unrelenting than any other where; and yet amid all these distressing circumstances, as we would think them, they were the most cheerful and apparently happy creatures on board. One, whose offence for which he had been sold was an over-fondness for his wife, played the fiddle almost continually; and the others danced, sung, cracked jokes, and played various games with cards from day to day. How true it is that “God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb,” or in other words, that He renders the worst of human conditions tolerable, while He permits the best, to be nothing better than tolerable.

Lincoln loathed slavery as far back as the late 1830s, but he rarely spoke out about the slavery question until the 1850s. There were several reasons for his silence, starting with his belief that the institution was dying out. In a response to Stephen A. Douglas in June 1858, he told a Chicago audience that the Republican Party was made up of people “who will hope for its ultimate extinction.” How could it not be so, he thought, given that slavery is morally wrong and politically unsustainable?

This belief proved to be naïve. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 had made it possible to separate cotton fibers from its seeds mechanically; previously this painstaking process was performed entirely by hand and involved hundreds of hours of manual, usually slave, labor. Most northern states had banned slavery, but most southern states saw an expansion of slavery correlated with the growth of “King Cotton.” With the separation (ginning) process speeding the rate of production, plantation owners could dramatically increase the acreage on which they grew cotton. As cotton acreage expanded, more and more slaves were needed for cultivation. Rather than being on the cusp of extinction, slavery was booming.

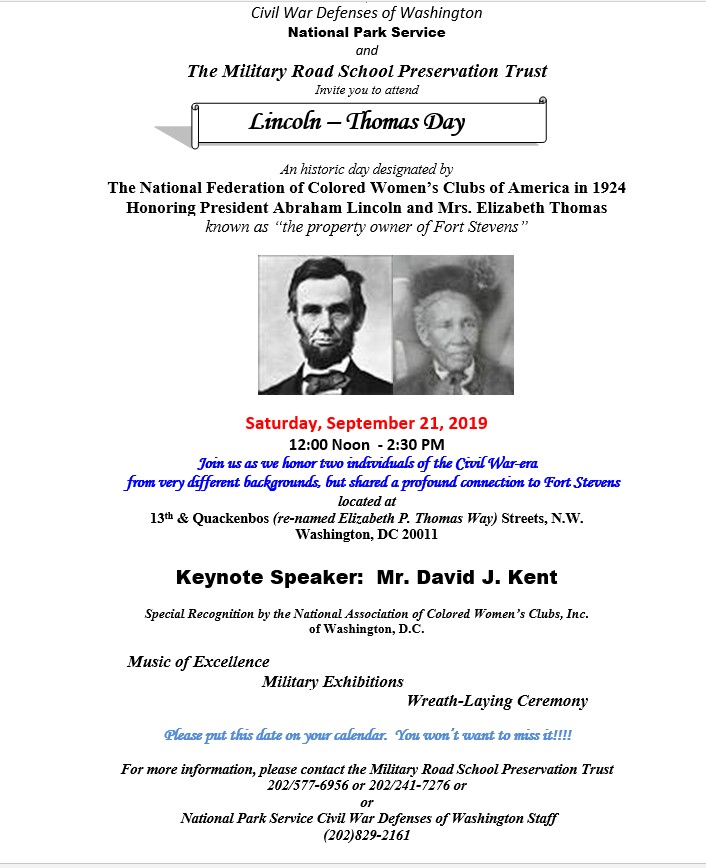

Once he recognized this reality, Lincoln focused on how to stop its expansion. I talked about some of the ways, in particular his long road to emancipation of enslaved people in the District of Columbia, during my recent keynote address on Lincoln-Thomas Day at Fort Stevens in the District. I talked about other ways in my book, Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America. I’ll have more on this website in the future.

[Partially adapted from Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America]

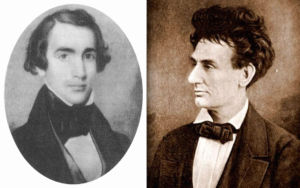

[Note: Photo is of Joshua Speed and Abraham Lincoln]

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

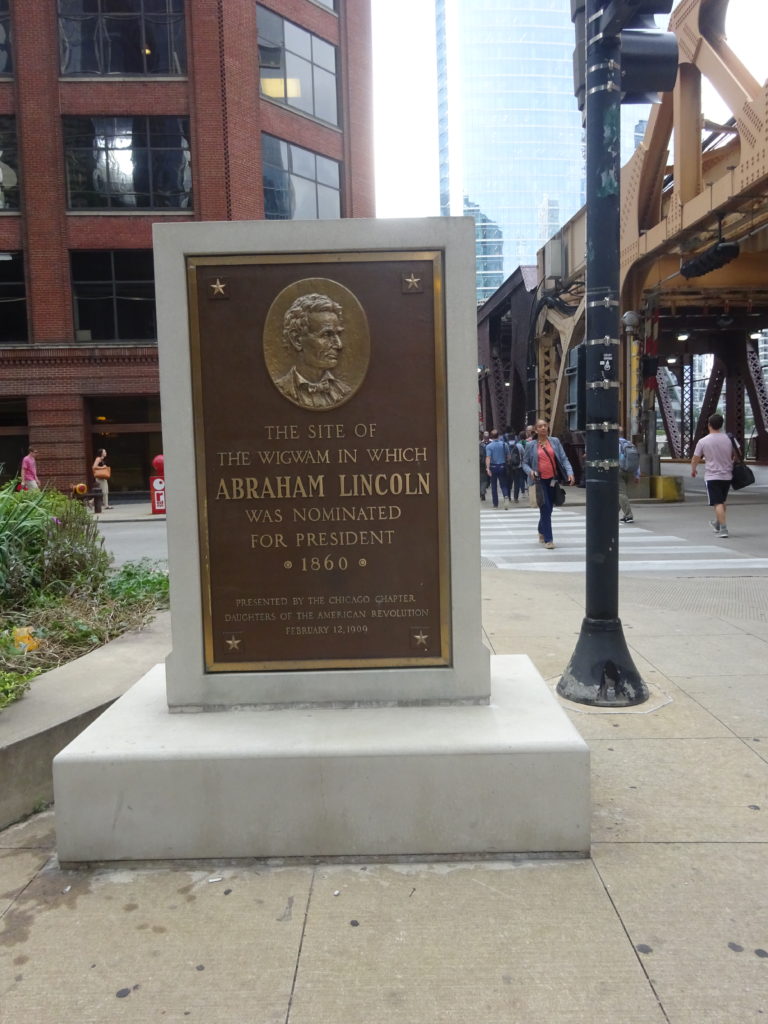

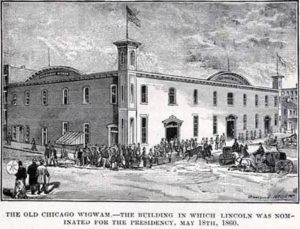

I’m currently chasing Abraham Lincoln’s wigwam, the name given to the building in which Lincoln received the Republican nomination for President in 1860. Here’s the backstory:

I’m currently chasing Abraham Lincoln’s wigwam, the name given to the building in which Lincoln received the Republican nomination for President in 1860. Here’s the backstory: It seems my travel this year has been heavy on places starting with “C.” Soon I’ll add Caribbean Cruise on one of the

It seems my travel this year has been heavy on places starting with “C.” Soon I’ll add Caribbean Cruise on one of the