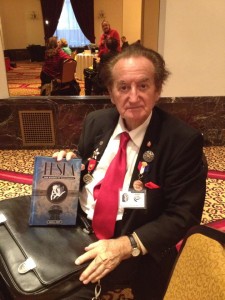

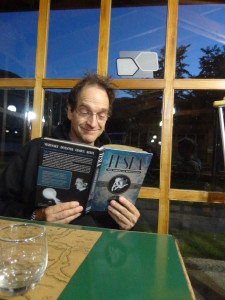

Those following this page know that I wrote a biography of famed Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla in 2013. Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity has gone on to become a great success. In fact, the third printing is due in Barnes and Noble stores this month (February 2015), which will help reach even more tens of thousands of people.

Those following this page know that I wrote a biography of famed Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla in 2013. Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity has gone on to become a great success. In fact, the third printing is due in Barnes and Noble stores this month (February 2015), which will help reach even more tens of thousands of people.

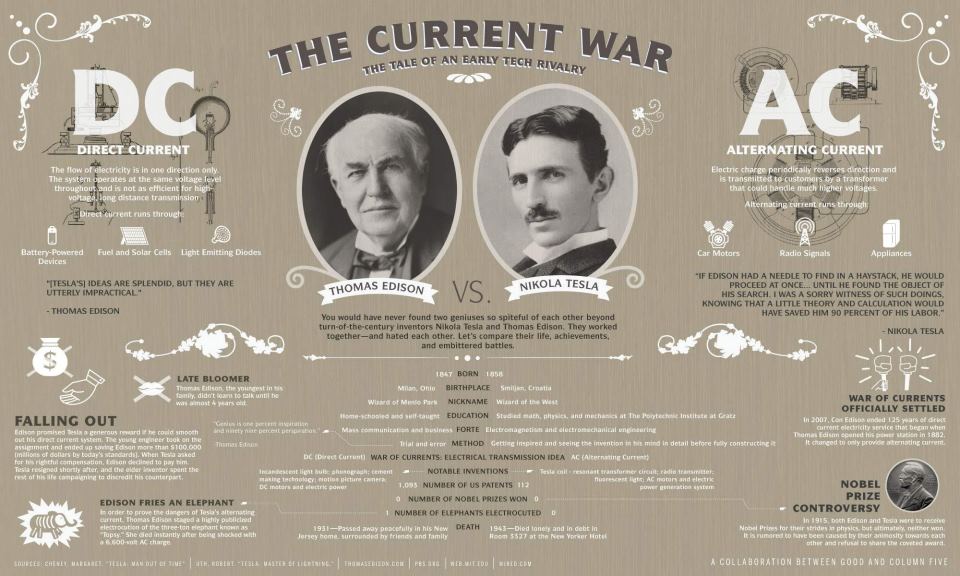

Every Tesla fan knows that he and Thomas Edison had a love/hate relationship. Initially colleagues and friends, they became rivals as Tesla hooked up with George Westinghouse to advance alternating current (AC) while Edison was deeply invested in direct current (DC). The chapter “A Man Always at War” in my Tesla book is filled with stories about the war of the currents.

Now it’s time for the another perspective.

I am happy to announce that Fall River Press, the imprint of Sterling Publishing that published Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity, has asked me to write a similarly styled book on none other than Thomas Edison!

Yes, that Thomas Edison.

Edison, of course, was well established as an inventor before Tesla arrived in New York. The new book will examine Edison’s life, his successful inventions, his failures, and his perspective on the war of the currents. The book will also delve into Edison’s invention factories in Menlo Park and West Orange, New Jersey, as well as his friendships – and rivalries – with some of the great personages of the time. The intent is to show Edison’s trials and tribulations as well as his triumphs.

Previous biographies of Edison have given Nikola Tesla very little mention. My book on Edison will bring Tesla into the picture where appropriate.

I’ll be working on the book this year and Fall River Press is planning to release it some time in 2016. I’ll update as soon as I have a more concrete schedule.

As I work on the book I can’t help but envision actor Tom Cappadona as Thomas Edison. Cappadona played Edison in the 2013 off-Broadway play TESLA, the cast of which I had the privilege of visiting about a month before the play’s opening. As a guest of the director I got to see TESLA on opening night, where an overflow house gave a sustained and enthusiastic standing ovation at the end of the show. Tom Cappadona was superlative in the role of Thomas Edison, so it’s his face that inspires my writing of the great inventor. [He’s also my first choice to cover the title role in the highly unlikely event that the book becomes a Steven Spielberg film (hey, I can dream, right?).]

I’ll have more information as the book develops, but expect the same style as my Tesla book – snappy writing, great photos, and an interesting look at a complicated man.

David J. Kent is the author of Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and the e-book Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time.

“Like” me on my Facebook author’s page and share the news with your friends using the buttons below. Also check me out on Goodreads.

So what has life been up to lately? Here on Science Traveler I did some science traveling into the lands of sea grass, alligators and iconic writers. I found out that

So what has life been up to lately? Here on Science Traveler I did some science traveling into the lands of sea grass, alligators and iconic writers. I found out that  Science Traveler also delved into the science of Lincoln’s interest in, well, science. In particular his use of

Science Traveler also delved into the science of Lincoln’s interest in, well, science. In particular his use of  Hot White Snow reminisced about

Hot White Snow reminisced about  The Dake Page took on two serious topics to help communicate science to the public.

The Dake Page took on two serious topics to help communicate science to the public.

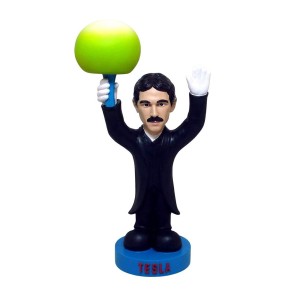

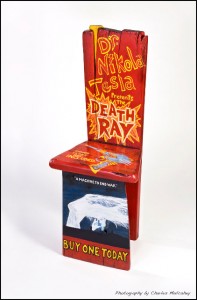

There are many other pop icon examples of Nikola Tesla as well. And you can help collect them. Post photos of Tesla as pop icon on my

There are many other pop icon examples of Nikola Tesla as well. And you can help collect them. Post photos of Tesla as pop icon on my  The main thesis of this book is that Abraham Lincoln’s greatness came from his mastery of the “six-books of Euclid” geometry, and the subsequent application of the six elements of Euclid into his logic, reasoning, and speeches.

The main thesis of this book is that Abraham Lincoln’s greatness came from his mastery of the “six-books of Euclid” geometry, and the subsequent application of the six elements of Euclid into his logic, reasoning, and speeches. Not literally, of course, but as the guide informed us during our tour, Hemingway let dozens of feral cats roam his grounds freely. Many of them had six toes, a condition called polydactyly for you scientist-types out there. I recalled from my marine biology days that sailors thought polydactyl cats were good luck, or at the very least were better at catching rats. In any case, Hemingway was given a six toed cat by a ship’s captain and well, cats breed. There are currently 40-50 cats on the Hemingway property, which the guides regularly trot out for photo-ops.

Not literally, of course, but as the guide informed us during our tour, Hemingway let dozens of feral cats roam his grounds freely. Many of them had six toes, a condition called polydactyly for you scientist-types out there. I recalled from my marine biology days that sailors thought polydactyl cats were good luck, or at the very least were better at catching rats. In any case, Hemingway was given a six toed cat by a ship’s captain and well, cats breed. There are currently 40-50 cats on the Hemingway property, which the guides regularly trot out for photo-ops.

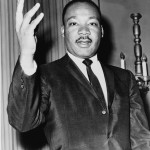

On this day we celebrate and honor the life of Martin Luther King, Jr. More importantly, we relive the struggle to break the institutionalized discrimination against a large percentage of our fellow Americans. As Lincoln once suggested in a different situation, it is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

On this day we celebrate and honor the life of Martin Luther King, Jr. More importantly, we relive the struggle to break the institutionalized discrimination against a large percentage of our fellow Americans. As Lincoln once suggested in a different situation, it is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.