|

The Lincoln Country: From These Humble Beginnings…to Immortality |

|

|

Abraham Lincoln Crossword Puzzles |

2014 |

| Bartelt, William E. and Claybourn, Joshua A. (Eds) |

Abe’s Youth: Shaping the Future President |

2019 |

| Bartelt, William E. and Claybourn, Joshua A. (Eds) |

Abe’s Youth: Shaping the Future President |

2019 |

| Bayard, Louis |

Courting Mr. Lincoln (A Novel) |

2019 |

| Bayne, Julia Taft |

Tad Lincoln’s Father |

2001 |

| Bennett, Jr., Lerone |

Forced Into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream |

1999 |

| Blumenthal, Sidney |

All the Powers of Earth 1856-1860: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 3 |

2019 |

| Blumenthal, Sidney |

All the Powers of Earth 1856-1860: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 3 |

2019 |

| Blumenthal, Sidney |

All the Powers of Earth 1856-1860: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 3 |

2019 |

| Bordewich, Fergus M. |

America’s Great Debate: Henry Clay, Stephen A. Douglas, and the Compromise that Preserved the Union |

2012 |

| Boritt, Gabor S. (ed) |

Of the People, By the People, For the People and other Quotations |

1996 |

| Brands, H.W. |

Heirs of The Founders: The Epic Rivalry of Henry Clay, John Calhoun, and Daniel Webster, The Second Generation of American Giants |

2018 |

| Brown, Thomas J. |

The Public Art of Civil War Commemoration: A Brief History with Documents |

2004 |

| Carden, Allen and Ebert, Thomas J. |

John George Nicolay: The Man in Lincoln’s Shadow |

2019 |

| Cartmell, Donald |

The Civil War Up Close |

2005 |

| Casson, Herbert N. |

Cyrus Hall McCormick: His Life and Work |

1971 |

| Chadwick, Bruce |

Lincoln For President: An Unlikely Candidate, An Audacious Strategy, and the Victory No One Saw Coming |

2009 |

| Conwell, Russell H. |

Why Lincoln Laughed |

1922 |

| Coulson, Thomas |

Joseph Henry: His Life & Work |

1950 |

| Delbanco, Andrew |

The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War |

2018 |

| Donald, David Herbert and Hozler, Harold (Eds) |

Lincoln in the Times: The Life of Abraham Lincoln as Originally Reported in the New York Times |

2005 |

| Efflandt, Lloyd H. |

Lincoln and the Black Hawk War |

1991 |

| Eifert, Virginia S. |

The Buffalo Trace |

1957 |

| Fehrenbacher, Don E. |

Lincoln in Text and Context: Collected Essays |

1987 |

| Fehrenbacher, Don E. and Fehrenbacher, Virginia (Compiled and Edited by) |

Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln |

1996 |

| Fleischner, Jennifer |

Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckley: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave |

2003 |

| Foot, Isaac |

Oliver Cromwell and Abraham Lincoln: A Comparison |

1944 |

| Freehling, William W. |

The South vs The South: How Anti-Confederate Southerners Shaped the course of the Civil War |

2001 |

| Gates, Henry Louis |

Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow |

2019 |

| Good, Timothy S. |

We Saw Lincoln Shot: One Hundred Eyewitness Accounts |

1995 |

| Grafton, John (Compiler and Historical Notes) |

Abraham Lincoln Great Speeches |

1991 |

| Guarneri, Carl J. |

Lincoln’s Informer: Charles A. Dana and the Inside Story of the Union War |

2019 |

| Guelzo, Allen C. |

Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President |

1999 |

| Handlin, Oscar and Lilian |

Abraham Lincoln and the Union |

1980 |

| Harris, Laurie Lanzen |

How to Analyze the Works of Abraham Lincoln |

2013 |

| Hirsch, David and Van Haften, Dan |

The Tyranny of Public Discourse: Abraham Lincoln’s Six-Element Antidote for Meaningful and Persuasive Writing |

2019 |

| Hirsch, David and Van Haften, Dan |

The Tyranny of Public Discourse: Abraham Lincoln’s Six-Element Antidote for Meaningful and Persuasive Writing |

2019 |

| Horner, Harlan Hoyt |

Lincoln and Greeley |

1953 |

| Jefferson, Thomas (edited and notes by David Waldstreicher) |

Notes on the State of Virginia |

2002 |

| Johannsen, Robert W. (Ed.) |

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 |

1965 |

| Kalten, D.M. |

The Duel: Abraham Lincoln and Rebecca |

2016 |

| Kantor, MacKinlay |

Andersonville |

1955 |

| Kimmel, Stanley |

Mr. Lincoln’s Washington: A Panorama of Events in Washington from 1861 to 1865 Taken From Local Newspapers and with over 250 Illustrations |

1957 |

| Klingaman, William K. and Klingaman, Nicholas P |

The Year Without Summer: 1816 and the Volcano That Darkened the World and Changed History |

2013 |

| Knoles, George Harmon (Ed) |

The Crisis of the Union |

1965 |

| Larson, John Lauritz |

Internal Improvement: National Public Works and the Promise of Popular Government in the Early United States |

2001 |

| Lonn, Ella |

Salt as a Factor in the Confederacy |

1965 |

| Lorant, Stefan |

Lincoln: A Picture Story of His Life |

1979 |

| Lowry, Thomas P. |

Don’t Shoot That Boy!: Abraham Lincoln and Military Justice |

1999 |

| Lundberg, James M. |

Horace Greeley: Print, Politics, and the Failure of American Nationhood |

2019 |

| McCormick, Cyrus |

The Century of the Reaper |

1931 |

| Meltzer, Milton (ed) and Alcorn, Stephen (illustrator) |

Lincoln in His Own Words |

1993 |

| Myers, James E. |

The Astonishing Saber Duel of Abraham Lincoln |

1969 |

| Nevins, Allan and Irving Stone (Eds) |

Lincoln: A Contemporary Portrait |

1962 |

| Olmstead, Frederick Law (with Arthur Schlesinger, Editor) |

The Cotton Kingdom: The Classic First-Hand Account of the Slave System in the Years Preceding the Civil War |

1969 |

| Patterson, Matt |

Union of Hearts: The Abraham Lincoln & Ann Rutledge Story |

2000 |

| Paull, Bonnie E. and Hart, Richard E. |

Lincoln’s Springfield Neighborhood |

2015 |

| Phillips, Ulrich B. |

Life & Labor in the Old South |

1963 |

| Puleo, Stephen |

American Treasures: The Secret Efforts to Save the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address |

2016 |

| Randall, J.G. |

Lincoln: The Liberal Statesman |

1947 |

| Randall, J.G. |

Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln |

1964 |

| Reninger, Marion Wallace |

My Lincoln Letter |

1953 |

| Rhoads, Mark Q. |

Land of Lincoln: Thy Wondrous Story: Through the Eyes of the Illinois State Society |

2013 |

| Roske, Ralph J. and Van Doren, Charles |

Lincoln’s Commando: The Biography of Commander W.B. Cushing, U.S.N. |

1957 |

| Shaw, Robert (photographer) and Burlingame, Michael (text) |

Abraham Lincoln Traveled This Way: The America Lincoln Knew |

2012 |

| Sideman, Belle Becker and Friedman, Lillian (Eds) |

Europe Looks at the Civil War |

1960 |

| Soodhalter, Ron |

Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader |

2006 |

| Spielvogel, J. Christian |

Interpreting Sacred Ground: The Rhetoric of National Civil War Parks and Battlefields |

2013 |

| Splaine, John |

A Companion to the Lincoln Douglas Debates |

1994 |

| Stephenson, Nathaniel Wright |

Abraham Lincoln and the Union, A Chronicle of the Embattled North |

1918 |

| Tagg, Larry |

The Battles that Made Abraham Lincoln: How Lincoln Mastered His Enemies to Win the Civil War, Free the Slaves, and Preserve the Union |

2012 |

| Taylor, John M. |

While Cannons Roared: The Civil War Behind the Lines |

1997 |

| Temple, Wayne C. |

“The Taste Is In My Mouth A Little…”: Lincoln’s Victuals and Potables |

2004 |

| Temple, Wayne C.; Edited by Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis |

Lincoln’s Confidant: The Life of Noah Brooks |

2019 |

| Varon, Elizabeth R. |

Armies of Deliverance: A New History of the Civil War |

2019 |

| Weber, Karl (Ed.) |

Lincoln: A President for the Ages (Companion Essays to the Movie) |

2012 |

| Weiner, Greg |

Old Whigs: Burke, Lincoln, and the Politics of Prudence |

2019 |

| Wert, Jeffry D. |

Civil War Barons: The Tycoons, Entrepreneurs, Inventors, and Visionaries Who Forged Victory and Shaped a Nation |

2018 |

| Wilson, Steven |

President Lincoln’s Spy |

2008 |

| Winkle, Kenneth J. |

The Young Eagle: The Rise of Abraham Lincoln |

2001 |

| Zimmerman, Dwight Jon; Illustrated by Wayne Vansant |

The Hammer and the Anvil: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the End of Slavery in America |

2012 |

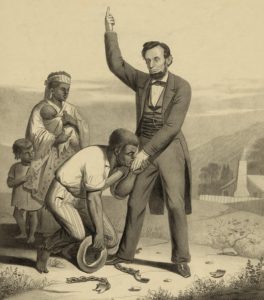

Abraham Lincoln signed the Compensated DC Emancipation bill into law about five months before he released his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. But that wasn’t the first time he tried to free enslaved people in the Washington, D.C.

Abraham Lincoln signed the Compensated DC Emancipation bill into law about five months before he released his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. But that wasn’t the first time he tried to free enslaved people in the Washington, D.C.

What a year in a writer’s life. I was incredibly busy this year even though I finished no new books. As I look back on

What a year in a writer’s life. I was incredibly busy this year even though I finished no new books. As I look back on  This was a big year in Abraham Lincoln book acquisitions. My average number of new books acquired has been a fairly consistent 58 books over each of the last five years. This year was 82. While that’s a big jump from my average, it still falls short of the 98 I acquired back in 2013.

This was a big year in Abraham Lincoln book acquisitions. My average number of new books acquired has been a fairly consistent 58 books over each of the last five years. This year was 82. While that’s a big jump from my average, it still falls short of the 98 I acquired back in 2013. St. Kitts is the larger of two islands that make up the nation of St. Kitts and Nevis. Nevis is most famous for being the birthplace of Alexander Hamilton, the musical about whom I recently saw in Chicago. While St. Kitts is now a tourist mecca, the island is best known for its dominant position in the colonial sugar trade. Lesser known is that St. Kitts also was a major hub in the slave trade.

St. Kitts is the larger of two islands that make up the nation of St. Kitts and Nevis. Nevis is most famous for being the birthplace of Alexander Hamilton, the musical about whom I recently saw in Chicago. While St. Kitts is now a tourist mecca, the island is best known for its dominant position in the colonial sugar trade. Lesser known is that St. Kitts also was a major hub in the slave trade. On September 27, 1841, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to

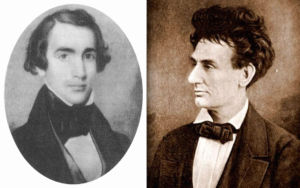

On September 27, 1841, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to  Abraham Lincoln didn’t see much slavery as a small child growing up in northern Kentucky, or through his formative years in Indiana. But he did get an introduction of sorts.

Abraham Lincoln didn’t see much slavery as a small child growing up in northern Kentucky, or through his formative years in Indiana. But he did get an introduction of sorts. This has been a very busy summer in Lincoln world. For me personally I have two upcoming presentations in Washington, D.C., including keynoting a major annual event at Fort Stevens. And both are free (so come on down).

This has been a very busy summer in Lincoln world. For me personally I have two upcoming presentations in Washington, D.C., including keynoting a major annual event at Fort Stevens. And both are free (so come on down). On April 4, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln took his son Tad into the city of Richmond, Virginia. The city had fallen the day before into Union hands two days before. It was Tad’s 12th birthday.

On April 4, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln took his son Tad into the city of Richmond, Virginia. The city had fallen the day before into Union hands two days before. It was Tad’s 12th birthday.

William Wallace Lincoln, “Willie,” died of typhoid fever on February 20, 1862. President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary Lincoln were devastated. Willie’s younger brother Tad was also afflicted, but would live. This personal tragedy on top of the ongoing Civil War was almost too much to bear for both of them; Mary would never completely recover. But Willie’s death, and those of 700,000 soldiers during the Civil War, also ushered in advances in the embalming sciences.

William Wallace Lincoln, “Willie,” died of typhoid fever on February 20, 1862. President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary Lincoln were devastated. Willie’s younger brother Tad was also afflicted, but would live. This personal tragedy on top of the ongoing Civil War was almost too much to bear for both of them; Mary would never completely recover. But Willie’s death, and those of 700,000 soldiers during the Civil War, also ushered in advances in the embalming sciences.