Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American falsely accused of flirting with a white woman, was lynched in 1955. George Floyd died under the knee of a police officer in 2020. Together, and with thousands of other examples and millions of cases, the long history of systemic racism continues in America. To provide some background, what follows is a brief outline of the history of systemic racism and discrimination in the United States.

Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American falsely accused of flirting with a white woman, was lynched in 1955. George Floyd died under the knee of a police officer in 2020. Together, and with thousands of other examples and millions of cases, the long history of systemic racism continues in America. To provide some background, what follows is a brief outline of the history of systemic racism and discrimination in the United States.

White Lion, 1619: Jamestown, the first permanent settlement of white Europeans on the continent that would become America, was visited by a privateer sailing ship called the White Lion. On board were several dozen Africans stolen from a Spanish slave ship San Juan Bautista, headed for Veracruz, New Spain (now part of Mexico). Some of the Africans were traded by the White Lion crew for food at Virginia Colony’s Point Comfort. Slavery had come to America.

U.S. Declaration of Independence, 1776: When Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence, it originally had a clause attacking slavery as something forced on the American colonies by the British rulers and an antithesis to the Declaration’s concept of “all men are created equal.” The clause was removed during debate as southern slaveholding states in conjunction with their northern merchant partners refused to agree.

U.S. Constitution, 1789: After several years under the wholly ineffective Articles of Confederation, delegates began working on a new constitution in 1787. The U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1788 and took effect March 4, 1789 with George Washington as the nation’s first president. Delegates engaged in significant debate about slavery, again with South Carolina and other southern states working with northern merchants to void any sections that would have eliminated slavery. Forced to compromise to get all the existing states to agree, the Constitution tacitly acknowledges the presence of slavery, although they took great pains to avoid using the words “slave” or “slavery” in the text, relying on euphemisms like “all other persons.” Article 1, Section 2 allows slaveholding states to count “three fifths of all other persons” (i.e., enslaved people) for purposes of determining the number of representatives in Congress. Article 1, Section 9 prohibits Congress from banning the “migration or importation of such persons” (i.e., the international slave trade) for 20 years. Article 4, Section 2 dictates that any “person held to labour or service” (i.e. slaves) in one state that escapes to another still remains a slave and must be returned. Thus, the Constitution, while many members wanted to eliminate slavery, tacitly acknowledges its continued presence.

Abolition of International Slave Trade, 1808: As noted above, the Constitution did not allow the end of the international slave trade for twenty years after the Constitution was ratified. In 1807, Congress, including some southern slaveholding states, voted to abolish the slave trade, effective January 1, 1808. Congress had already banned slavery in the northwest territories via the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 (a few months prior to the Constitution). While slavery still existed, there were actions taken in an attempt to encourage its demise.

Antebellum Period, 1789-1860: Many of the founders believed that slavery was on a path to its “ultimate extinction.” The formal end of the international slave trade, the banning of slavery in the territories, and the gradual elimination of slavery in the northern states seemed to signal that end. However, Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin made it more profitable to grow cotton in the South. As smaller farms were bought up by rich plantation owners, more acreage was planted, thus requiring more enslaved people for labor. In addition, the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 doubled the land area available for expansion. The Mexican War in 1847 again enlarged the nation by a third, now essentially making the United States a coast-to-coast nation. As these territories formed into states, they provided potential new plantations, but more importantly, new slaveholding power in Congress. A series of compromises attempted to deal with “the slavery question” inherent in this western expansion. All of these compromises provided continued power to slave states, which simultaneously threatened to secede if new power was not extended to them. As slavery expanded, it became more and more likely that a peaceful resolution of the slavery issue was not possible.

Civil War, 1861-1865: Led by South Carolina, the southern slaveholding states seceded from the Union, claiming that the election of “Black Republican” Abraham Lincoln was an attack on slavery despite Lincoln’s insistence (and the 1860 Republican platform) that no attempt would be made to ban slavery from those states in which it existed. In fact, Lincoln and most Republicans believed that the Constitution barred federal authorities from abolishing slavery. As had occurred with all the northern states that enacted state legislation to remove slavery, Lincoln and Congress knew that it was up to the individual southern states to choose to do the same. And yet the war came. In the midst of the war, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure, knowing that it had authority only during a time of insurrection and would become moot once the war ended. All of the southern states stated that slavery was the cause of their secession and the war, and that they believed that whites were superior to blacks, and that this was the natural order of things. John C. Calhoun had declared a decade earlier that the highest form of civilization was a chain of hierarchy from master to slave, and that slavery was “a positive good.” Alexander Stephens, former Congressman and newly elected as the Confederate Vice President, declared in his “Cornerstone” speech that the Confederacy was born of the belief that the nation’s “foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery – subordination to the superior race – is his natural and normal condition.” White supremacy and racism was officially codified.

13th, 14th, 15th Amendments, 1865-1870: Lincoln understood that the Emancipation Proclamation was a temporary measure and immediately began lobbying Congress to pass the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. As anyone who has seen Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln movie knows, Lincoln forcefully pushed for passage of an amendment to forever ban slavery from the United States. After his assassination, the 14th Amendment provided for citizenship and equal protection under the law to all persons born or naturalized in the United States. The 15th Amendment declared that no citizen shall be denied the right to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” These amendments were an attempt to protect the rights of formerly enslaved people, free blacks, and all American citizens.

Reconstruction, 1863-1877: Even before the war was over, Lincoln began the process of reconstructing the United States by defining the conditions under which the former Confederate states could be brought back into the Union. States that had been entirely or partially reclaimed by Union forces (e.g., Louisiana) were supported in their efforts to reestablish themselves. Following the war, states had to acknowledge the sovereignty of the federal authority and ratify the 13th amendment. Free and formerly enslaved African Americans were protected under the three reconstruction amendments, began work and education to allow them to exist as free men and women, eagerly embraced their right to vote, and ran for local, state, and national office. Unfortunately, over time the North lost interest in protecting their rights (the South showed no interest from the beginning) and those rights slowly eroded away. As W.E.B. Dubois put it, “the slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

Jim Crow/Segregation/White Supremacy, 1877-1965: As the rights supposedly guaranteed under Reconstruction faded, white Americans began a system of blatant racism and white supremacy designed to keep black Americans from getting “too uppity.” As under the slave hierarchy, black men and women were treated by individuals, then groups, then by governments as inferior. Several supposedly “Christian” organizations, including the Ku Klux Klan, grew as a means of keeping the black population “in their place.” This was blatant white supremacy and systemic racism enforced through terrorist activities like cross burning and lynching, as well as by unfair “separate but equal” facilities. Black men like Emmett Till were summarily hanged without trial simply for the “crime” of not being subservient enough to white people. Local law enforcement and conservative politicians often were the leaders of the KKK and lynchings were codified into both practice, and in many cases, the law. Separate but equal, which needless to say wasn’t actually equal, became the law of the land, as had slavery once been.

Civil Rights Acts, 1964-1965: Through the persistence of African American civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, President John F. Kennedy proposed and Lyndon Johnson pushed through the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Civil Rights Act ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The Voting Rights Act of 1865 sought to eliminate the barriers that state and local governments had erected to prevent African Americans from exercising their right to vote. One hundred years after emancipation and the right to freedom was established, African Americans were still attempting to be treated as equal under the law.

Shelby County v. Holder, 2013: In 2013, the Republican-controlled U.S. Supreme Court eliminated a key section of the Voting Rights Act that required states with a history of discrimination to get pre-clearance prior to making changes to their voting laws. This provision was necessary because many states (primarily what today we call “red states”) long had used Jim Crow and other laws to keep minorities from voting. Immediately after the Supreme Court eliminated the provision, supposedly because “it was no longer needed,” many states enacted laws that do exactly what the Court had suggested would not happen (which everyone, in fact, knew would happen). States began systematically putting up barriers to voting by minorities, including requiring special IDs while eliminating the local offices in which they could be obtained. Suddenly voting precincts in minority areas were eliminated, forcing voters to travel long distances and wait for many hours in long lines. Precincts in areas dominated by white and affluent voters were expanded. Hundreds of thousands of voters were summarily eliminated from voter rolls in minority-dominant areas. Gerrymandering was expanded to an extreme to ensure Republicans would win more seats even when receiving fewer votes. Systemic racism had joined forces with voter suppression.

Today: George Floyd is the most recent of many high profile cases in which black men and women have been killed as a result of either police action or racist hate crimes. The difference today is that everyone now carries a portable video camera in their smart phone. In many cases we see that the official police report falsely describes the incident, which begs the question as to how much systemic discrimination goes uncaptured on video. In many respects it appears that Jim Crow, segregation, and lynching have returned, and indeed are being encouraged, by the Trump administration. But it goes beyond these overt results of discrimination. African American men and women have been disproportionately imprisoned due to unequal laws, enforcement, and sentencing practices. Employment discrimination increases the risk of poverty. Systemic racism, poverty, and injustice has led to significantly higher risks of death and disease. The list goes on.

The brief history above is given to allow people a better understanding of today’s situation. Protests in the streets are not solely because of the death of one man, or even the many men and women who have died under questionable circumstances. The problem is that this has been going on in one form or another for the entire history of the United States, and before. Whether we admit it or not, racism and discrimination are built into our society. It’s systemic. The only way to fix it is to eliminate it from our societal construct. Redlining, voter suppression, politicians stoking fears of “the other”; all are systemic racism.

Given the attitudes and abuses of the Trump administration and Republican Party leadership, the only solution is to vote. Those protesting (and risking their lives given our current COVID pandemic) need to get to the polls. Voter suppression tactics will try to keep minorities, women, the poor, and others from voting, especially in an election where the coronavirus may limit the ability to vote in-person. All of us must vote. Only by eliminating those who encourage racism, both by individuals and the system, can we make the systemic changes that will ensure that all men and women are treated equally.

[Photo Credit: StanleyFormanPhotos.com; Called “The Soiling of Old Glory,” the photo won the 1977 Pulitzer Prize]

David J. Kent is an avid science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

Like this:

Like Loading...

On June 19th, 1865, Union Major General Gordon Granger entered Galveston, Texas and discovered that somehow word had not previously been communicated to the enslaved people that they were free in accordance with Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation effective January 1, 1863. With Granger’s General Order No. 3, June the 19th came to represent the end of slavery in America, and as such became an African American holiday called Juneteenth.

On June 19th, 1865, Union Major General Gordon Granger entered Galveston, Texas and discovered that somehow word had not previously been communicated to the enslaved people that they were free in accordance with Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation effective January 1, 1863. With Granger’s General Order No. 3, June the 19th came to represent the end of slavery in America, and as such became an African American holiday called Juneteenth.

Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American falsely accused of flirting with a white woman, was lynched in 1955. George Floyd died under the knee of a police officer in 2020. Together, and with thousands of other examples and millions of cases, the long history of systemic racism continues in America. To provide some background, what follows is a brief outline of the history of systemic racism and discrimination in the United States.

Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American falsely accused of flirting with a white woman, was lynched in 1955. George Floyd died under the knee of a police officer in 2020. Together, and with thousands of other examples and millions of cases, the long history of systemic racism continues in America. To provide some background, what follows is a brief outline of the history of systemic racism and discrimination in the United States. On April 11, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln gave his

On April 11, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln gave his  Samuel Clemens, known to most of us by his pseudonym Mark Twain, was born in Hannibal, Missouri on November 30, 1835, shortly after Halley’s Comet had made its regular but rare pass by the Earth. The 26-year-old Abraham Lincoln – an amateur astronomy buff who two years earlier had marveled at the Leonid meteor showers – may very well have been gazing at the skies when Mark Twain came into this world. At that age Lincoln lived in New Salem, Illinois, just a stone’s throw across the Mississippi River from Hannibal. In 1859, Lincoln rode the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad to give a speech in Council Bluffs, Iowa. The railroad just happened to be formed in the office of Mark Twain’s father thirteen years before.

Samuel Clemens, known to most of us by his pseudonym Mark Twain, was born in Hannibal, Missouri on November 30, 1835, shortly after Halley’s Comet had made its regular but rare pass by the Earth. The 26-year-old Abraham Lincoln – an amateur astronomy buff who two years earlier had marveled at the Leonid meteor showers – may very well have been gazing at the skies when Mark Twain came into this world. At that age Lincoln lived in New Salem, Illinois, just a stone’s throw across the Mississippi River from Hannibal. In 1859, Lincoln rode the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad to give a speech in Council Bluffs, Iowa. The railroad just happened to be formed in the office of Mark Twain’s father thirteen years before. Lincoln floated flatboats down the Mississippi River to New Orleans as a young adult, then took steamboats back upriver. He often piloted steamboats around shoals near his New Salem home. Mark Twain had worked on steamboats on the river for much of his younger years, first as a deckhand and then as a pilot. Being a riverboat pilot gave him his pen name; “mark twain” is “the leadsman’s cry for a measured river depth of two fathoms (12 feet), which was safe water for a steamboat.” In 1883 Twain even titled his memoir, Life on the Mississippi. As we have already seen, Lincoln’s time traveling on and piloting steamboats eventually inspired his patent for lifting boats over shoals and obstructions on the river.

Lincoln floated flatboats down the Mississippi River to New Orleans as a young adult, then took steamboats back upriver. He often piloted steamboats around shoals near his New Salem home. Mark Twain had worked on steamboats on the river for much of his younger years, first as a deckhand and then as a pilot. Being a riverboat pilot gave him his pen name; “mark twain” is “the leadsman’s cry for a measured river depth of two fathoms (12 feet), which was safe water for a steamboat.” In 1883 Twain even titled his memoir, Life on the Mississippi. As we have already seen, Lincoln’s time traveling on and piloting steamboats eventually inspired his patent for lifting boats over shoals and obstructions on the river. Abraham Lincoln is best known for his Emancipation Proclamation, Gettysburg Address, and saving the Union during the Civil War. But in this Black History Month it’s important to remember that Lincoln also pushed for black voting rights.

Abraham Lincoln is best known for his Emancipation Proclamation, Gettysburg Address, and saving the Union during the Civil War. But in this Black History Month it’s important to remember that Lincoln also pushed for black voting rights.

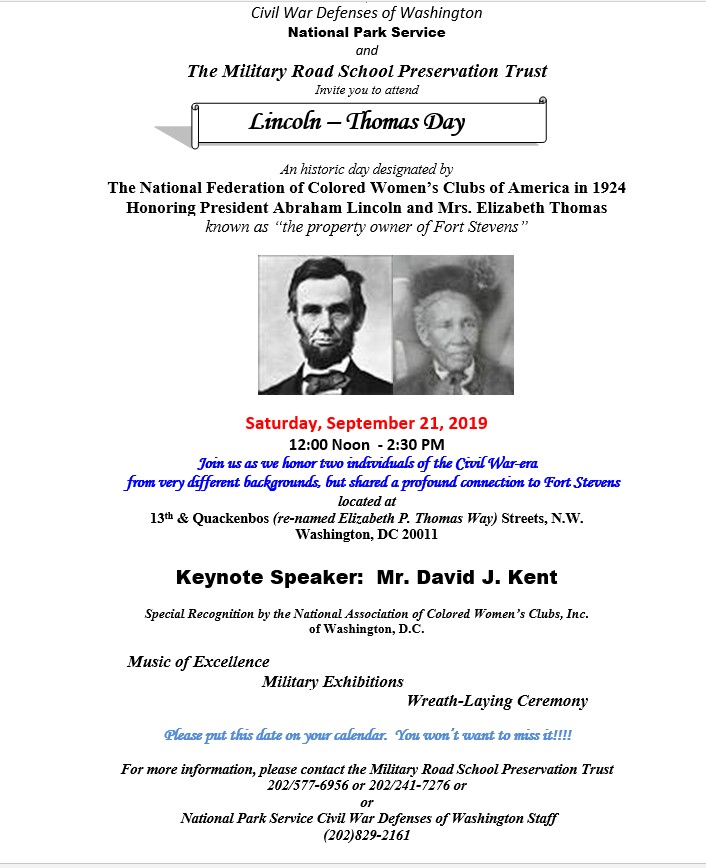

This has been a very busy summer in Lincoln world. For me personally I have two upcoming presentations in Washington, D.C., including keynoting a major annual event at Fort Stevens. And both are free (so come on down).

This has been a very busy summer in Lincoln world. For me personally I have two upcoming presentations in Washington, D.C., including keynoting a major annual event at Fort Stevens. And both are free (so come on down). It’s official. The room once used by Abraham Lincoln has been designated the Lincoln Room by House Resolution 1063. It’s a fitting tribute both to the 16th President of the United States and to Past-President of the Lincoln Group of DC, John Elliff. I was privileged to attend the dedication ceremony on May 1, 2019 in Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

It’s official. The room once used by Abraham Lincoln has been designated the Lincoln Room by House Resolution 1063. It’s a fitting tribute both to the 16th President of the United States and to Past-President of the Lincoln Group of DC, John Elliff. I was privileged to attend the dedication ceremony on May 1, 2019 in Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

John Quincy Adams was the sixth president of the United States. What many people do not know is that after his presidency he was elected to the US House of Representatives, where he served for 18 more years. He died on February 23, 1848 on the House floor during Abraham Lincoln’s one term as a US Congressman. Lincoln served on Adams’s funeral committee.

John Quincy Adams was the sixth president of the United States. What many people do not know is that after his presidency he was elected to the US House of Representatives, where he served for 18 more years. He died on February 23, 1848 on the House floor during Abraham Lincoln’s one term as a US Congressman. Lincoln served on Adams’s funeral committee. In December 1862 President Abraham Lincoln was in the midst of a Civil War, his Emancipation Proclamation was due to take effect in a few weeks, and he was struggling to maintain some sense of our national meaning. What he wrote in his message to Congress (equivalent to today’s State of the Union address) gives us lessons on how we should handle our current crisis.

In December 1862 President Abraham Lincoln was in the midst of a Civil War, his Emancipation Proclamation was due to take effect in a few weeks, and he was struggling to maintain some sense of our national meaning. What he wrote in his message to Congress (equivalent to today’s State of the Union address) gives us lessons on how we should handle our current crisis.