Things were not looking good for Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party in 1864. The populace was fatigued from over three years of bloody war with no end in sight. Lincoln had finally found a general “who fights” in Ulysses S. Grant, but even Grant was bogged down with a series of inconclusive – and horribly bloody – battles in the Wilderness, Petersburg, the Crater, Cold Harbor. And where the heck was William Tecumseh Sherman, who had gone radio-silent in his march across the South.

Things were not looking good for Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party in 1864. The populace was fatigued from over three years of bloody war with no end in sight. Lincoln had finally found a general “who fights” in Ulysses S. Grant, but even Grant was bogged down with a series of inconclusive – and horribly bloody – battles in the Wilderness, Petersburg, the Crater, Cold Harbor. And where the heck was William Tecumseh Sherman, who had gone radio-silent in his march across the South.

Then there was the Republican in-fighting. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase was intriguing behind the scenes to undermine Lincoln’s nomination for reelection. And the Radical Republicans thought Lincoln was too moderate on slavery and racial equality and may not win a second term. Even Lincoln was having doubts. The uncertainty led to a splitting of the party, at least temporarily, and two conventions that were each Republican but called something else.

While Chase backed down, the Radicals in the party sought an alternative candidate. Coming together in Cleveland in May 1864, the Radical Republicans rebranded as the Radical Democracy Party. They nominated the Republican Party’s 1856 presidential nominee, John C. Fremont for president and War Democrat John Cochrane for vice president. Their platform called for a continuation of the war without compromise, a constitutional amendment banning slavery and authorizing equal rights, confiscation of rebel property, congressional control of reconstruction, and a one-term limit on the presidency.

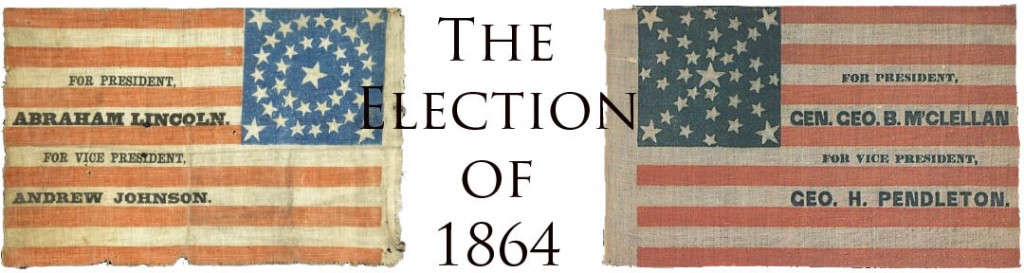

A week later, the rest of the Republican Party, especially those who supported Lincoln for a second term, met on June 7-8, 1864, in Baltimore. Feeling pressured by the split in their own party (with memories of how the Democrats had split in 1860 into Northern and Southern factions, thus ensuring their loss), the Lincoln Republicans sought to broaden their appeal and reflect the national character of the war while providing a place for War Democrats. Like the other Republican faction, this one rebranded itself into the National Union Party. They nominated Abraham Lincoln for president and Democrat Andrew Johnson as vice president. The party platform made many of the same points as the Radical Republicans had, including winning the war, destruction of the Confederacy, and a constitutional amendment ending slavery (although not equal rights or a one-term limit). All parts of the Republican Party agreed on the basic principles, if not some of the more contentious details.

The change in vice presidents was driven by the perceived need to present a more inclusive party. Baltimore convention delegates felt that Hannibal Hamlin, Lincoln’s first vice president, was superfluous. Vice presidents had little to do anyway, but by 1864 the state of Maine was firmly for the union, meaning Hamlin would not bring any substantive new voting cohort to the ticket. Hamlin had leaned more radical, yet had been, and no doubt would have continued to be, loyal to the Lincoln administration. But the delegates felt outreach to the Democrats necessary to assure reelection. Andrew Johnson, at least on paper, seemed a perfect fit. A senator from Tennessee when the war started, he was the only southern senator to remain loyal to the United States when his state seceded. Lincoln would make him the territorial governor of Tennessee during the war, at least that part that had been recaptured by Union forces. Johnson also talked a good game when it came to being hard on the Southern elite he despised (mostly because he had been a poor tailor, and they were rich landowners). He seemed a textbook companion candidate, especially since he likely would not have much of a role for the next four years. That choice would come back to haunt the party and the nation.

So now the Republicans/National Union Party had Lincoln in place to run for a second term. That still left John C. Fremont out there as a potential spoiler. Fremont was not all that happy with Lincoln, who had unceremoniously rescinded Fremont’s emancipation order early in the war and removed him from service. But as the summer progressed, the Radical Republicans/Radical Democracy Party failed to get much traction. None of the Republican newspapers supported Fremont and most Republicans continued to back Lincoln for reelection. Then on September 2, 1864, General Sherman resurfaced to announce he had captured Atlanta on his “march to the sea.” Realizing their lack of support, and that being a spoiler would be disastrous, Fremont and Cochrane withdrew from the race on September 21, 1864. Fremont remained critical of Lincoln, and, behind the scenes, his withdrawal may have been part of a deal with Lincoln in which Radical Republicans forced the removal of Postmaster General Montgomery Blair from the cabinet.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party, now driven entirely by Southern slave interests, managed to shoot itself in the foot (so to speak). They fervently backed a party platform calling for an end of the war at all costs, most likely by a negotiated peace with no end to slavery and recognition of the Confederacy as a separate country. They then nominated Lincoln’s former General-in-Chief, George B. McClellan for president. McClellan immediately disavowed his own party’s platform to avoid looking like the Democrats were ready to dismiss the sacrifices all who gave their lives in the war (some 750,000 combined). McClellan’s renunciation was effectively negated by the Democrats’ choice of George H. Pendleton as the vice-presidential nominee. Pendleton was a protégé of Clement Vallandigham, leader of the Copperhead faction of the Democratic Party, a faction seen by many as traitorous to the Union.

By early fall, Lincoln’s chances started to seem much better.

Still, the election is never over until the votes are cast. The people still had to vote, and many of them were out in the trenches fighting a war.

Coming in February 2026: Unable to Escape This Toil

Lincoln: The Fire of Genius: How Abraham Lincoln’s Commitment to Science and Technology Helped Modernize America is available at booksellers nationwide.

Limited signed copies are available via this website. The book also listed on Goodreads, the database where I keep track of my reading. Click on the “Want to Read” button to put it on your reading list. Please leave a review on Goodreads and Amazon if you like the book.

You also follow my author page on Facebook.

David J. Kent is President of the Lincoln Group of DC and the author of Lincoln: The Fire of Genius: How Abraham Lincoln’s Commitment to Science and Technology Helped Modernize America and Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America.

His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity andEdison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

A shocking

A shocking  As the Civil War raged on, things weren’t looking so good for the reelection of Abraham Lincoln. In August 1864 Lincoln asked his entire cabinet to sign the back of what became the “

As the Civil War raged on, things weren’t looking so good for the reelection of Abraham Lincoln. In August 1864 Lincoln asked his entire cabinet to sign the back of what became the “