Abraham Lincoln was a big fan of technology and used the telegraph as a war-management tool during the Civil War. The value of the telegraph was reinforced daily. Lincoln received many messages over the new Pacific and Atlantic telegraph that began operation in October of 1861, including one from Governor-Elect Leland Stanford on October 26, 1861 noting, “Today California is but a second’s distance from the national Capital.” Stanford went on to become president of the Central Pacific Railroad, the western leg of the transcontinental railroad system Lincoln signed into existence in 1862. The first transcontinental telegraph message was sent from California Chief Justice Stephen Field in San Francisco to Lincoln in Washington over the Western Union telegraph lines. Lincoln would appoint Field as the newly created tenth U.S. Supreme Court justice.

Abraham Lincoln was a big fan of technology and used the telegraph as a war-management tool during the Civil War. The value of the telegraph was reinforced daily. Lincoln received many messages over the new Pacific and Atlantic telegraph that began operation in October of 1861, including one from Governor-Elect Leland Stanford on October 26, 1861 noting, “Today California is but a second’s distance from the national Capital.” Stanford went on to become president of the Central Pacific Railroad, the western leg of the transcontinental railroad system Lincoln signed into existence in 1862. The first transcontinental telegraph message was sent from California Chief Justice Stephen Field in San Francisco to Lincoln in Washington over the Western Union telegraph lines. Lincoln would appoint Field as the newly created tenth U.S. Supreme Court justice.

But first he needed access. When the war started there was no telegraph line running to the War Department offices next to the White House, never mind into the president’s mansion itself.

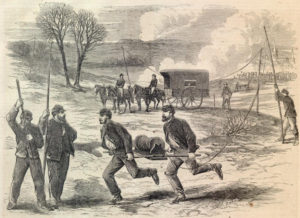

As the First Battle at Bull Run raged, aging and largely immobile General-in-Chief Winfield Scott took a nap, accustomed to the traditional lack of communication during battles. Lincoln was more intent for news, spending hours in the War Department while army engineers like Andrew Carnegie strung telegraph wires into northern Virginia, never quite reaching the front as men on horseback rushed to deliver information. A year later, at the second battle near Bull Run Creek, Lincoln was actively monitoring telegraph messages as the battle ensued. According to Bates, “when in the telegraph office, Lincoln was most at ease of access. He often talked with the cipher-operators (all messages were put into codes), asking questions about the dispatches which were translating from or into cipher.”

Lincoln was aided by the fact that he appointed Thomas A. Scott, vice president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, as assistant secretary of war, along with Edward S. Sanford, president of the American Telegraph Company, whom he put in charge of military telegraphs. Similar to what he did with railroads using the power of congressional acts, Lincoln effectively nationalized the country’s telegraph network and put it under control of the military. Lincoln used the telegraph sparingly early in the war, sending no more than twenty telegrams throughout 1861. But after taking control in early 1862, Lincoln became an avid reader and sender of telegrams to more actively manage generals in the field, in particular those like McClellan who seemed eager to train troops but not to use them in combat.

Lincoln occasionally used telegrams to vent his frustration, most often at General McClellan. In early October 1862, a month after the Battle of Antietam, with little or no movement on the part of McClellan’s army, Lincoln wrote a long letter that included: “You know I desired . . . you to cross the Potomac below, instead of above the Shenandoah and Blue Ridge. My idea was that this would at once menace the enemies’ communications, which I would seize if he would permit.” He laid out specific goals and strategies regarding cutting off communications, and then should the opportunity exist, “try to beat him to Richmond on the inside track.” All too familiar with McClellan’s tendency not to fight, Lincoln added, “I say ‘try’; if we never try, we shall never succeed.” When McClellan complained about tired horses, Lincoln shot back by telegraph: “I have just read your dispatch about sore tongued and fatigued horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigue anything?” Lincoln removed McClellan from command a few weeks later.

Lincoln’s influence on the spread of telegraphy was not finished. In his 1862 Annual Message to Congress, he indicated a preference for connecting the United States with Europe by an Atlantic telegraph, as well as a similar project to extend the Pacific telegraph between San Francisco and the Russian empire. Not only was Lincoln the first to use the telegraph extensively in wartime, he made sure that the telegraph became a key tool of diplomacy and communication in the peacetime that followed.

[Adapted from Lincoln: The Fire of Genius]

[Photo Credits: all by David J. Kent, 2023]

Lincoln: The Fire of Genius: How Abraham Lincoln’s Commitment to Science and Technology Helped Modernize America is available at booksellers nationwide.

Limited signed copies are available via this website. The book also listed on Goodreads, the database where I keep track of my reading. Click on the “Want to Read” button to put it on your reading list. Please leave a review on Goodreads and Amazon if you like the book.

You also follow my author page on Facebook.

David J. Kent is President of the Lincoln Group of DC and the author of Lincoln: The Fire of Genius: How Abraham Lincoln’s Commitment to Science and Technology Helped Modernize America and Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America.

His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World and two specialty e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Disheveled as he was when he showed up on the doorstep of the venerable Western Union Company, Edison was confident that management would see through the rough exterior into his insightful mind. The company had made a name for itself even before the Civil War, but the rampant use of telegraphy during the conflict enabled Western Union to grow immensely, swallowing up its nearest competitors and becoming a force in the industry. This was just the opportunity Edison was looking for. During his initial interview, office manager George Milliken was so impressed with the 21-year-old that he hired him immediately. Milliken asked how soon Edison would be ready to work, to which Edison replied “Now.” He was put to work on the shift that day at 5:30 p.m.

Disheveled as he was when he showed up on the doorstep of the venerable Western Union Company, Edison was confident that management would see through the rough exterior into his insightful mind. The company had made a name for itself even before the Civil War, but the rampant use of telegraphy during the conflict enabled Western Union to grow immensely, swallowing up its nearest competitors and becoming a force in the industry. This was just the opportunity Edison was looking for. During his initial interview, office manager George Milliken was so impressed with the 21-year-old that he hired him immediately. Milliken asked how soon Edison would be ready to work, to which Edison replied “Now.” He was put to work on the shift that day at 5:30 p.m. In October 1861, California Chief Justice Stephen Johnson Field reportedly sent a message to Abraham Lincoln via the newly completed transcontinental telegraph. The event was a milestone that predated the later transcontinental railroad.

In October 1861, California Chief Justice Stephen Johnson Field reportedly sent a message to Abraham Lincoln via the newly completed transcontinental telegraph. The event was a milestone that predated the later transcontinental railroad.