| Anderson, Dwight G. |

Abraham Lincoln: The Quest for Immortality |

1982 |

| Barber, Lucius W. |

Army Memoirs of Lucius W. Barber, Company “D,” 15th Illinois Volunteer Infantrym May 24, 1861 to Sept. 30, 1865 |

1894 |

| Berg, Scott W. |

38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier’s End |

2012 |

| Boritt, Gabor |

The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech That Nobody Knows |

2006 |

| Boritt, Gabor S. (ed) |

The Lincoln Enigma: The Changing Faces of an American Icon |

2001 |

| Boothe, F. Norton |

Great Generals of the Civil War and Their Battles |

1986 |

| Bowman, John S. |

The Civil War Day By Day: An Illustrated Almanac of America’s Bloodiest War |

1989 |

| Brandt, Nat |

The Town That Started the Civil War |

1990 |

| Briggs, John Channing |

Lincoln’s Speeches Reconsidered |

2005 |

| Brown, William Wells |

The Negro in the American Rebellion: His Heroism and His Fidelity |

1971 |

| Brownstein, Elizabeth Smith |

If This House Could Talk |

1999 |

| Brownstein, Elizabeth Smith |

Lincoln’s Other White House: The Untold Story of the Man and His Presidency |

2005 |

| Bush, Bryan S. |

Lincoln and the Speeds: The Untol Story of a Devoted and Enduring Friendship |

2008 |

| Cannan, John |

The Crater: Burnside’s Assault on the Confederate Trenches, June 30, 1864 |

2002 |

| Campbell, R. Thomas |

Gray Thunder: Exploits of the Confederate States Navy |

1996 |

| Catton, Bruce |

The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War |

1960 |

| Catton, Bruce |

The Army of the Potomac: Mr. Lincoln’s Army |

1962 |

| Catton, Bruce |

The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road |

1952 |

| Catton, Bruce |

The Army of the Potomac: A Stillness at Appomattox |

1953 |

| Catton, Bruce |

Gettysburg: The Final Fury |

1974 |

| Clinton, Catherine |

Mrs. Lincoln: A Life |

2009 |

| Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, III and Walton H. Owen, II |

Mr. Lincoln’s Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington |

1988 |

| Cornwell, Bernard |

Battle Flag |

1995 |

| Cromie, Alice |

A Tour Guide to the Civil War: The Complete State-by-State Guide to Battlegrounds, Landmarks, Museums, Relics, and Sites (3rd Edition, Revised) |

1990 |

| Davis, William C. |

Rebels & Yankees: The Commanders of the Civil War |

1990 |

| Delbanco, Andrew (Ed) |

The Portable Abraham Lincoln |

1992 |

| DeRose, Chris |

Congressman Lincoln: The Making of America’s Greatest President |

2013 |

| Deutsch, Kenneth L. and Fornieri, Joseph R. (Eds) |

Lincoln’s American Dream: Clashing Political Perspectives |

2005 |

| Duffy, James P. |

Lincoln’s Admiral: The Civil War Campaigns of David Farragut |

2006 |

| Ecelbarger, Gary |

The Great Comeback: How Abraham Lincoln Beat the Odds to Win the 1860 Republican Nomination |

2008 |

| Eliot, Alexander |

Abraham Lincoln: An Illustrated Biography |

1985 |

| Eliot, Alexander |

Abraham Lincoln: An Illustrated Biography |

1985 |

| Epstein, Daniel Mark |

The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage |

2008 |

| Findley, Paul |

A. Lincoln: The Crucible of Congress |

1979 |

| Fletcher, George P. |

Our Secret Constitution: How Lincoln Redefined American Democracy |

2001 |

| Gary W. Gallagher (Ed) |

Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander |

1989 |

| Gary, Ralph |

Following in Lincoln’s Footsteps: A Complete Annotated Reference to Hundreds of Historical Sites Visited by Abraham Lincoln |

2001 |

| Halleck, Henry Wager |

Elements of Military Art and Science |

1862 |

| Hartwig, D. Scott |

To Antietam Creek: The Maryland Campaign of September 1862 |

2012 |

| Haythornthwaite, Philip |

Unforms of the Civil War in Color |

1990 |

| Henderson, G.F.R., C.B. |

Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War |

1993 |

| Henig, Gerald S. and Niderost, Eric |

Civil War Firsts: The Legacies of America’s Bloodiest Conflict |

2001 |

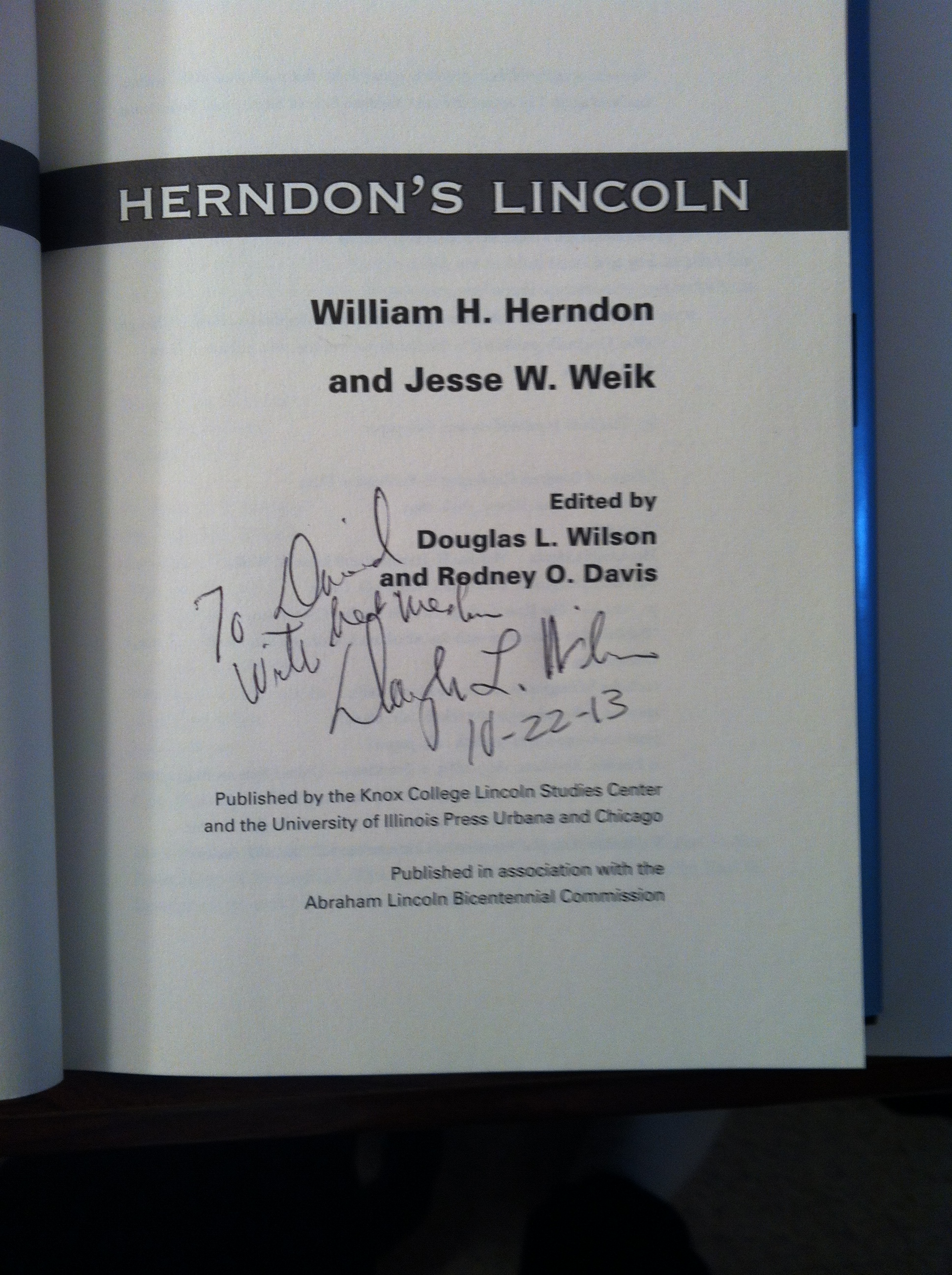

| Herndon, William H. and Weik, Jesse William |

Herndon’s Life of Lincoln |

1943 |

| Hicks, Brian and Kropf, Schuyler |

Raising the Hunley: The Remarkable History and Recovery of the Lost Confederate Submarine |

2002 |

| Hirsch, David and Van Haften, Dan |

Barack Obama, Abraham Lincoln, and the Structure of Reason |

2012 |

| Holzer, Harold |

Lincoln: President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter 1860-1861 |

2008 |

| Holzer, Harold and the New York Historical Society |

The Civil War in 50 Objects |

2013 |

| Illinois Central Railroad Company |

Abraham Lincoln As Attorney for the Illinois Central Railroad Company |

1905 |

| Jahns, Patricia |

Matthew Fontaine Maury & Joseph Henry: Scientists of the Civil War |

1961 |

| Jahns, Patricia |

Joseph Henry: Father of American Electronics |

1970 |

| Jordan, Robert Paul |

The Civil War |

1969 |

| Keneally, Thomas |

Abraham Lincoln |

2003 |

| Knauer, Kelly (Ed) |

Abraham Lincoln An Illustrated History of His Life and Times |

2012 |

| Kostyal, K.M. |

Field of Battle: The Civil War Letters of Major Thomas J. Halsey |

1996 |

| Kushner, Tony |

Lincoln: The Screenplay |

2012 |

| Lachman, Charles |

The Last Lincolns: The Rise & Fall of a Great American Family |

2008 |

| Lamon, Ward H. |

The Life of Abraham Lincoln; From His Birth to his Inauguration as President (Illustrated Edition) |

2013 |

| Lee, Richard M. |

Mr. Lincoln’s City: An Illustrated Guide to the Civil War Sites of Washington |

1981 |

| Lehrman, Lewis E. |

Lincoln “by littles” |

2013 |

| Lewis, Lloyd |

The Assassination of Lincoln: History and Myth |

1994 |

| Lind, Michael |

What Lincoln Believed: The Values and Convictions of America’s Greatest President |

2004 |

| Livingston, Mary P. (Ed) |

A Civil War Marine at Sea: The Diary of Medal of Honor Recipient Miles M. Oviatt |

1998 |

| Logan, John A. |

The Great Conspiracy: Its Origin and History |

1895 |

| Long, E.B. with Barbara Long |

The Civil War Day By Day: An Almanac: 1861-1865 |

1971 |

| Lowry, Rich |

Lincoln Unbound: How an Ambitious Young Railsplitter Save the American Dream – And How We Can Do It Again |

2013 |

| Marvel, William (ed) |

The Monitor Chronicles: One Sailor’s Account: Today’s Campaign to Recover the Civil War Wreck |

2000 |

| MCPherson, James M. |

Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era |

1988 |

| McPherson, James M. |

The Negro’s Civil War: How American Blacks Felt and Acted During the War for the Union |

1991 |

| Menge, W. Springer and Shimrak, J. August |

The Civil War Notebook of Daniel Chisholm: A Chronicle of Daily Life in the Union Army 1864-1865 |

1989 |

| Meredith, Roy |

Mr. Lincoln’s Camera Man: Mathew B. Brady |

1974 |

| Milton, George Fort |

Abraham Lincoln and the Fifth Column |

1942 |

| Mitgang, Herbert |

The Fiery Trial: A Life of Lincoln |

1974 |

| Mitgang, Herbert (ed) |

Abraham Lincoln: A Press Portrait |

1971 |

| Monaghan, Jay |

The Man Who Elected Lincoln |

1956 |

| Moore, Edward A. |

The Story of a Cannoneer Under Stonewall Jackson |

1907 |

| Morse, John T. |

On Becoming Abraham Lincoln: From the 1893 Biography |

2008 |

| Musicant, Ivan |

Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War |

1995 |

| Neely, Mark E. Jr. |

The Last Best Hope of Earth: Abraham Lincoln and the Promise of America |

1993 |

| Nesbitt, Mark |

Ghosts of Gettysburg: Spirits, Apparitions and Haunted Places of the Battlefield |

1991 |

| Nofi, Albert A. (Compiler) |

A Civil War Journal: A Fascinating Collection of Facts, Episodes & Anecdotes |

1995 |

| Prokopowicz, Gerald J. |

Did Lincoln Own Slaves? And Other Frequently Asked Questions About Abraham Lincoln |

2008 |

| Redkey, Edwin S. (Ed) |

A Grand Army of Black Men |

1992 |

| Sandburg, Carl |

Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years |

1954 |

| Sandburg, Carl |

Storm Over the Land: A Profile of the Civil War |

1939, 1942 |

| Schwartz, Gerald (Ed) |

A Woman Doctor’s Civil War: Esther Hill Hawks’ Diary |

1984 |

| Scripps, John Locke |

Vote Lincoln! The Presidential Campaign Biography of Abraham Lincoln, 1860 |

2010 |

| Simson, Jay W. |

Naval Strategies of the Civil War: Confederate Innovations and Federal Opportunism |

2001 |

| Spiegel, Allen D. |

A. Lincoln: Esquire: A Shrewd, Sophisticated Lawyer in His Time |

2002 |

| Splaine, John |

A Companion to the Lincoln Douglas Debates |

1994 |

| Still, William N., Jr., Taylor, John M., and Delaney, Norman C. |

Raiders and Blockaders: The American Civil War Afloat |

1998 |

| Styple, William B. (Ed) |

Tell Me of Lincoln: Memories of Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War & Life in Old New York by James E. Kelly |

2009 |

| Swanson, James L. |

Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer |

2006 |

| Tarbell, Ida M. |

The Life of Abraham Lincoln |

1924 |

| Wert, Jeffry D. |

The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac |

2005 |

| Wideman, John C. |

Naval Warfare: Courage and Combat on the Water |

1997 |

| Wilson, Douglas L. |

Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews, and Statements about Abraham Lincoln |

1998 |

| Winkler, H. Donald |

Lincoln’s Ladies: The Women in the Life of the Sixteenth President |

2004 |

| Wynalda, Stephen A. |

366 Days in Abraham Lincoln’s Presidency: The Private, Political, and Military Decisions of America’s Greatest President |

2010 |

I hope everyone is having a great holiday break. I’ll be back with more on Nikola Tesla later, but here’s a mini book review of The Crater by John Cannan (just published on Goodreads).

I hope everyone is having a great holiday break. I’ll be back with more on Nikola Tesla later, but here’s a mini book review of The Crater by John Cannan (just published on Goodreads).

There are over 15,000 books that have been written about Abraham Lincoln. At least that’s the number that is bandied about whenever someone talks about Lincoln books. Whether that number includes books about the Civil War or just books focused on Lincoln himself is also in question. In any case, I have over 800 titles, with more than 95% specific to the man, not the war.

There are over 15,000 books that have been written about Abraham Lincoln. At least that’s the number that is bandied about whenever someone talks about Lincoln books. Whether that number includes books about the Civil War or just books focused on Lincoln himself is also in question. In any case, I have over 800 titles, with more than 95% specific to the man, not the war. As I do research on Abraham Lincoln for a forthcoming book I periodically post reviews of some of the more interesting and relevant Lincoln scholarship. Which led me to this great book dating back to 1956 called Lincoln and the Tools of War by Robert V. Bruce.

As I do research on Abraham Lincoln for a forthcoming book I periodically post reviews of some of the more interesting and relevant Lincoln scholarship. Which led me to this great book dating back to 1956 called Lincoln and the Tools of War by Robert V. Bruce.

So 2013 was an incredible year, and 2014 is already looking like it will be even more incredible. Later this month I’ll take a look back on all that has happened this past year. Meanwhile, my event schedule for 2014 is starting to take shape. Here are just a few of the events already on the calendar for the first six to eight months:

So 2013 was an incredible year, and 2014 is already looking like it will be even more incredible. Later this month I’ll take a look back on all that has happened this past year. Meanwhile, my event schedule for 2014 is starting to take shape. Here are just a few of the events already on the calendar for the first six to eight months: ? – What is this…nothing on my calendar yet for June? I’ll need to do something about that soon.

? – What is this…nothing on my calendar yet for June? I’ll need to do something about that soon. Abraham Lincoln once gave a speech that was so awe-inspiring that all the reporters there forgot to write it down. Sounds implausible, right? Ah, but it’s actually true. Elwell Crissey takes us back to May 29, 1856 with “Lincoln’s Lost Speech: The Pivot of His Career.” And despite the little problem of not having a record of the actual speech, Crissey does a great job enlivening the whole event surrounding its presentation.

Abraham Lincoln once gave a speech that was so awe-inspiring that all the reporters there forgot to write it down. Sounds implausible, right? Ah, but it’s actually true. Elwell Crissey takes us back to May 29, 1856 with “Lincoln’s Lost Speech: The Pivot of His Career.” And despite the little problem of not having a record of the actual speech, Crissey does a great job enlivening the whole event surrounding its presentation. One would think the book’s subtitle “The speech that made Abraham Lincoln President,” would set up an unattainable expectation of greatness. After all, how could a book hold a candle to a great speech? Or perhaps the speech wasn’t so great after all and the author merely wanted to sell more books. And yet, I was wonderfully surprised to see that this really was an exceptional book about an exceptional speech.

One would think the book’s subtitle “The speech that made Abraham Lincoln President,” would set up an unattainable expectation of greatness. After all, how could a book hold a candle to a great speech? Or perhaps the speech wasn’t so great after all and the author merely wanted to sell more books. And yet, I was wonderfully surprised to see that this really was an exceptional book about an exceptional speech. Vote Lincoln! The Presidential Campaign Biography of Abraham Lincoln is a 2010 annotated version of the first full biography of Abraham Lincoln published in 1860. Ostensibly written by John Locke Scripps, publisher of what would become the Chicago Tribune, much of the text was actually ghost written by Abraham Lincoln himself. Intended as a campaign biography, the book provides a revealing look at how Lincoln viewed his own life to that point.

Vote Lincoln! The Presidential Campaign Biography of Abraham Lincoln is a 2010 annotated version of the first full biography of Abraham Lincoln published in 1860. Ostensibly written by John Locke Scripps, publisher of what would become the Chicago Tribune, much of the text was actually ghost written by Abraham Lincoln himself. Intended as a campaign biography, the book provides a revealing look at how Lincoln viewed his own life to that point.